Musings

Somehow the stars aligned and this morning we joined a private tour of the restored house of Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar (the son). The man is revered for many things, including drafting the secession papers for the state of Mississippi (leading up to the Civil War), then becoming “rehabilitated” (essentially) after the war, becoming not only a member of the US House of Representatives, but also a member of the US Supreme Court. He is still the only Mississippian to have served on that court.

This is the ancient osage orange that survives next to the house Lamar built on 30 ac on the outskirts of Oxford MS, named for Oxford GA and Oxford in England. The town has now crept up to the front yard, and the four-square house is now on what seems like a city lot. Even on a rainy day, it’s a special place, and worth the time to visit.

This monumental tree in the side yard was a total surprise. It’s an ancient and outsized osage orange tree.

Posted at 10:22 PM |

Comments Off on Unexpected histories

Found this derelict cooling facility that made an ice-company’s insulated rooms cold…while wandering the not-yet-abandoned industrial district of a contracting second-order (maybe third?) central place in the rural south….

Do you remember having concentration like this? When playing on the floor was a natural thing and your knees didn’t creak….

More evidence of concentration, this time by the elder offspring in the family we’re visiting…make your own board game! And you should see her pencil sketches…such talent! I’m in awe….

Posted at 11:48 PM |

2 Comments »

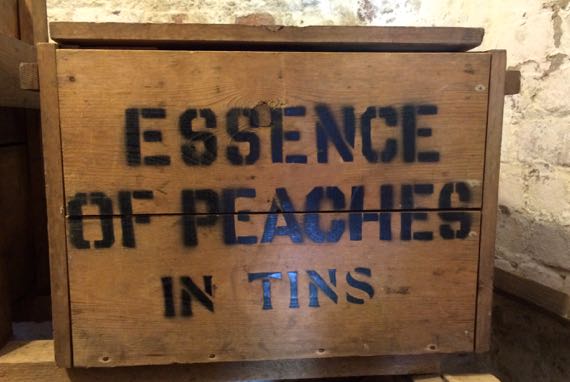

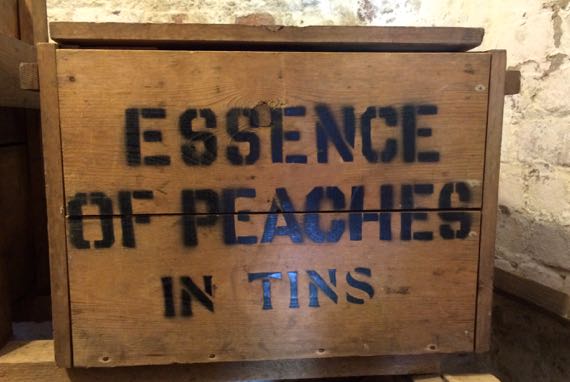

Wooden box at Fort Jackson yesterday.

I am not sure what was in the “Essence of Peaches” tins; was it peach puree? whole peach chunks? the equivalent of what we call peach nectar today?

Posted at 10:22 PM |

Comments Off on Mystified

Recommend the show at Fort Jackson, next time you’re in Savannah. The sign of US80 says “Cannon Firings!!!” Pay attention to the three exclamation points…it’s our theory that that’s the major clue…. Our fellow in blue (reenactor) was FAN-tastic, and got all of us “volunteers” to march and otherwise participate. Sooooooo fun.

Posted at 9:58 PM |

Comments Off on I reenacted (without the scratchy wool clothing)

Drayton Hall, c. 1750 (but for over a century believed to date a decade earlier), mantel detail.

We visited the American version of the English version of Classical Greek/Roman decorative arts. Not sure what mythical moment this is honoring, maybe…let’s look at flowers because it’s really cold out…thankfully sunny, but still cold.

A little chemistry and political economy…. In the depression that followed the Civil…umhem, War between the States, an economic downturn that lasted for about six decades in the Charleston (SC) area, savvy landholders benefitted from mining calcium phosphate along the Ashley River and nearby (upstream of Charleston). The calcium phosphate was processed to make particularly rich agricultural fertilizer. By the 1880s, the phosphate from this field dominated world production. But it didn’t last long…new fields discovered in Florida were easier to mine, and there were other market shifts.

Enough of this…sleep tight.

Posted at 9:32 PM |

1 Comment »

I’m still grooving on the golden leaves in the back yard (garden, British English).

Speaking of over the pond, I did a bit of research on brochs (auto-spell wisdom wants to make it brooches—a totally different thing) and wheelhouses today. Man, those archaeologists of Scotland’s past can nitpick. That’s a bit unfair; if they started with the data we have today, they’d generate a rather different initial interpretation (this is a constant problem/predicament in archaeo).

Posted at 9:30 PM |

Comments Off on Power of data

In the basement of one of the museums we visited was a large exhibit of ancient Roman coinage. This was some of the early stuff, dating to the 4th–3rd Cs BC. They look heavy to me.

Posted at 7:40 PM |

Comments Off on Pocket change

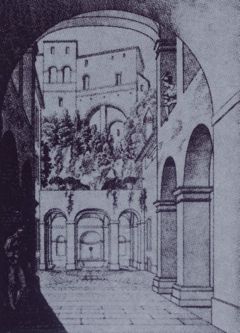

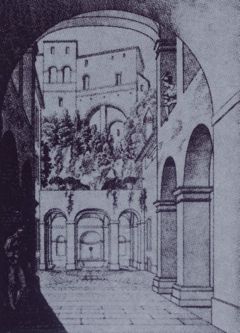

This is a nymphaeum that probably dates to very early in the 18th C. It’s right up against the foot of the Capitoline hill, just down from the staircase that ascends to the piazza that dominates the top of the hill at present.

Anciently, the Capitoline was a very important place in Rome. The first fortress was here, along with the first temples. Long story short, Mousse-oh-lee-nee chopped the north end off a hill that had already been greatly altered over the years, including the addition of a church in Medieval times and the 16th-C alterations of palazzos that now are part of the Capitoline Museums around the Piazza del Campidoglio, all designed by Michelangelo. This construction changed the ascent to the main hilltop from the east and the Forum to the west and the city. The climb from the Forum to the Capitoline summit was the last, and arguably the most important, part of the route of Triumphal processions that Republican and Imperial generals lead through the city, ending at a temple on the Capitoline where sacrifices were made.

Nymphaeums were first sacred springs where nymphs were believed to reside. Nymphs were likely part of the pantheon of pre-Roman peoples of the northern Italian Peninsula—and probably beyond. Eventually, springs were created in the form of fountains to evoke such sacred places (the water alternative to sacred groves). The name continued to be used for a contemplative location (garden) with flowing water, so that owners of a villa had one built in the back of their garden in the early 18th C, below ruins on the face of the Capitoline. Note how the vertical support in the arch above was there in the 18th C (drawing). Also, note the row of buildings (residences?) along the rim of the hillside, where there is now an overlook.

One other thing, apparently although the destruction in the 1920s didn’t remove the wall of the nymphaeum, the water supply was cut. In, get this, 2011, it was restored and a plaque installed noting this proud fact. And a mere three years later, it now looks like it’s been a barely functional oozing fountain for a half-century….

We splurged on a taxi to our overnight down at the airport that we hope will make an early arrival at the airport tomorrow easy (well, easier). The taxi was a Peugeot, oooh-lah-lah.

And we’re seeing a slushy, romantic, Julia Roberts promotion of Calzedonia, a big Italian company (clothing at least) play over and over on the TV (haven’t had TV for a while). Big Euro-bucks to the former Georgian, I’m sure.

WEATHER REPORT: Storms in NW Italy and SE France have sent mud and sludge into many towns, including Vernazza, which has been evacuated. No rain here, and overcast even has been spotty. Our trip planner (me) sure miscalculated the temperatures we’d experience during this trip; it’s been sweaty-hot much of the time, with pleasant cool evenings, mostly; however, we’ve been lucky with the rain, only a morning or so during our first stint in Rome….

Posted at 4:25 PM |

Comments Off on Later ruin

Yeah, it’s one massive ruin.

Spectators did not experience the interior of the Flavian Amphitheatre as anything like this. There was finish—cladding (mostly travertine) on the walls, staircases and access archways, statuary to remind visitors of gods and men (and probably goddesses and women), and most of the surface you see here was really seating, aisles, and arched entries. There was a cloth shade-cover that could be unfurled. So, no, it didn’t look like this. It’s like a skeleton compared to a living body. (Sorta.)

Drawing from several sources, this is what I conclude…. Spectators entered for free with tickets specifying a seating area, and some events lasted for days. The inauguration, in AD 80, lasted for 100 days, and later the stage area was modified so it could be flooded and used for nautical battles. A typical spectacle began with a morning opening parade (pompa), followed by fights between wild animals, hunts by armed men of animals, and shows of tamed animals. The experience of the latter was augmented by stunning scenes of their wild habitats. There was a break midday, used for executions. The goriest were damnatio ad bestias, in which the condemned were torn apart by wild animals. There’s no evidence that Christians were punished here in this manner. Between the major events, people played gambling games and postured to impress. [I tried a vertical panorama, an experiment; since the camera/phone can tell what’s “up” I didn’t know if it’d work—it did! The distortion is interesting, bowing the very vertical walls.]

Regarding the spectacles in the Colosseum, Claridge (2010:317–318) notes:

Gladiatorial shows were called munera (dutiful gifts) and were always given by individuals, not by the State. By the time the Colosseum was built they were being held as a regular public event, in December, as part of the New Year ritual, coinciding with the yearly political cycle, when they would be paid for by the incoming magistrates. At other times they could accompany the funerary rites for major public figures, or could be held on the anniversaries of past deaths. They were also staged in celebration of military triumphs. Such was their popularity that from the reign of Domitian it was decreed that in Rome they could only be given by the emperor; and elsewhere they required his sanction. The daily programme was usually divided into three parts: wild animal hunts (venationes) in the morning, public executions at midday, and gladiatorial contests in the afternoon; shows could run for many days depending on the available number of animals and gladiators. Trajan is said to have celebrated his Dacian triumph in AD 107 with 11,000 animals and 10,000 gladiators in the course of 123 days. Gladiators were a mixture of condemned criminals and prisoners of war (who were generally expendable), and career professionals (slaves, freedmen, or free volunteers), mostly men but occasionally women, specialized in different types of armour and weaponry: the heavily armed Myrmillo (named after the fish on his helmet) and the Samnite both had large oblong shields and swords; the more lightly armed Thracian, a round shield and curved scimitar; the Retiarius only a net and a trident. Others fought from chariots (essedarii), or on horseback. The fights were often staged in elaborate sets, with movable trees and buildings; the executions might involve complicated machinery and torture; some acted out particularly gruesome episodes from Greek or Roman mythology. Animals for the venationes came mainly from Africa and might include rhinoceros, hippos, elephants, and giraffes, as well as lions, panthers, leopards, crocodiles, and ostriches.

An observation: Romans use rear balconies like back porches, for storage and not-quite-so-public activities. Of course, it hosts plenty of drying laundry, plus often hot-water heaters are on the walls, piping the hot water inside—they’re the boxes on the walls. Here’s what I’ve been chuckling about: people store ladders there. Apparently, with high ceilings, people need ladders once in a while, and there is no “ladder for the building” or ladder that can be rented out from a nearby business. So many apartments have a ladder, and the place to store it is on the rear balcony (there’s one above the gate leaning next to the water heater).

An hour on a Friday afternoon…: we took a break using seating framing the church entry area part of the Piazza in front of the Chiesa di San Salvatore in Lauro, north of where we used to stay. We discovered several things. We saw two nursing moms take a break down from us on the same seating, each to feed their young-un while Pops idly stood by the stroller. No modesty cloths, just doing what needs doing. We also enjoyed the children playing out front, hopscotch and a bit of soccer-ball footwork. Then, at 5:30, the church bells began pealing, and Friday evening mass got underway. Music emanated. The kids kept playing. Then, just before 6, a procession formed in the doorway to the left of the church door. In the front were fully adult men carrying the cross and I don’t know what else—they make altar “boys” old here…. The group emerged and made a loop into the church, with the somewhat tottering highest-ranking fellow (judging by the tall headdress) at the end with two flanking attendees. No one told the little boy to stop and pick up his soccer ball, but he did. He was much more focused on the ritual than the group of girls. What you don’t see is that two of the nannies watching the kids looked like middle-aged Filapina ladies. Behind the officials, several toursts surged in, drawn by the pomp. We kept sitting and watching.

Claridge, Amanda, 2010. Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Posted at 4:35 PM |

2 Comments »

I scored. Thanks to my fine husband for being so game and for making it happen.

Yesterday was Ostia; today was…the Palatine Hill and Rome’s Forum!!! Actually, we saw a huge civic-ceremonial center, elite domestic compounds, roads and alleys, and some commercial activity areas.

The sun angle/intensity makes it seem like we were out there after dark, but no. This is the famous Aedes Saturnus, or Temple of Saturn. This version dates to AD 283, and is at least the third incarnation of a structure honoring this deity in this location. The first was back in the times of the earliest ceremonial buildings, traditionally considered the 5th C BC.

This building housed the city’s treasury, maintained by elected public officials called quaestors. Notes Stamper (2008:37):

Because Rome’s economy was based on agricultural production, such a temple dedicated to the cycle of the seasons and the growing and harvesting of crops was important. The notion of divine embodiment in the seasonal death and rebirth was essential to the agrarian culture, a tradition that related to Demeter in the Greek world, the primary divinity associated with crops. A statue of Saturn that stood inside the cella was wrapped with woolen bonds which were undone of the day of the feast, December 17, an event that

included a ceremonial sacrifice, with senators and knights dressed in togas, and a banquet that ended with the chant “Io Saturnalia.” Like the feast day of Jupiter, it was a day of festive gaiety, with shops, schools, and law courts closed, an event that became a yearly holiday. Ceremony, festivity, honor, and gaiety all became distinguishing features of the events surrounding the cult temples. Although none matched the importance of the events associated with the cult of Jupiter, they nevertheless imitated their style and intensity of spirit, becoming a defining characteristic of Roman culture.

With the line of standing columns, the eye is drawn to this ruin in the immediate area of the core of the Forum. It faced the Comitium, where the senate made decisions about the funds held in the Temple. It had three adjacent cellae, and was accessed via a long flight of stairs (now gone), as the floor was on an unusually high podium. Only parts of the front portico, with eight columns and part of the pediment, still stand. The surviving columns are of stone of many types, robbed from different structures. This recycling process is called spolia. The remaining portion of the architrave shows a frieze of acanthus leaves and palmettes; it dates to about 30 BC, and probably was salvaged from the burned, second version of the temple.

This is the lower peristyle garden (open courtyard within the compound) of the Domus Augustus, which drapes across the southeastern Palatine Hill. The upper peristyle garden contains a hexagon pattern, in a shallow hardscape design. This one is to the south and east of the upper one, and at least 5 meters below it (my guess). The hardscaping is a bit more 3D, and the blue flowers really make it pop. The complex is immense, and dates to AD 92. Augustus himself was said to inhabit the same bedroom for more than four decades, so I don’t know what his household did with the rest of the vast square footage of the Domus complex.

Originally, when, as a younger man known as Octavian, he moved to the Palatine and began construction, his house originally was designed in an unusual way resembling those of Hellenistic dynasties, with two courtyards and public and private zones. However, Octavian stopped construction, struck, it is reported, by a thunderbolt from Apollo, and had that structure razed. Upon the rubble a new construction begun that was three times the size (where did he get the area—by reducing gardens? razing other structures?). The new complex was over 22,000 m2 (over 5.4 ac), had a domus publica and a private area combined to make the Domus Augusti. It had a curia, two libraries, a porch supported by one hundred columns and decorated with statues of mythical Danaids, and a giant terraced wing to connect it with the Circus Maximus. The latter allowed him to process to his viewing area without mingling with the crowds.

He had a temple to Apollo to his complex, further increasing the symbolic weight of his complex. Notes Foubert (2010:67–68):

From the ancient sources it clearly appears that Augustus also attributed an important role to his wife in the elevation of his residence from the private to the public sphere. Suetonius states that Augustus presented his house as a stage of matronal display, claiming that the clothes he wore were hand-made by Livia and his daughter and granddaughters, thus associating them with one of the activities par excellence of an ideal Roman matrona. Her role as a supervising mater familias in the upbringing of several children living with her in the Augustan residence confirmed her role as an exemplary matron. It is known that Caligula and Claudius, among others, spent their childhood under Livia’s care and that other imperial children had received teachers from Livia’s household staff. These examples clearly show that until his death Augustus deliberately attempted to create a lieu de mémoire on the Palatine and that he believed that Livia had her role to play.

Other than the vast scale of this complex, it’s hard to even guess at the rest while strolling the dusty walkways where the public is allowed to venture. I could not guess at the function of most of the enclosed space, beyond the desire to impress.

To go a different direction, there are small features across this area of great importance, or at least being the physical embodiment linked to complex tales. That circular feature centered behind the center pair of poles is called the Lacus Curtius. It’s actually within the actual limits of the ancient Forum; a much larger area is typically termed “The Forum” today. The Lacus Curtius is an ancient feature of the Forum, and like others ancient constructions here, its original form and symbolism are now unknown. Livy gives an early story about this feature, in which the Lacus Curtius was the original pool/swamp here. Plutarch describes it as very muddy, enough to trap a horse. Varro wrote that it was consecrated in 445 BC. Titus Livius described it as a deep chasm amidst the Forum, which was reputed to never to be filled, unless by Rome’s most precious thing. A young knight, Marcus Curtius, the legend goes, then rode his horse into the abyss in sacrifice, to remedy this. A marble bas-relief portraying this scene was discovered nearby in 1553.

This area was excavated in April 1903 by workers directed by Giacomo Boni (whose grave is atop the Palatine). The Lacus has two layers of base slabs topped by a travertine layer surrounded by a curb. It had a parapet wall to set it off, set into pits remaining in the curb. The shape is now trapezoidal, and its form in Caesarian times and before is undetermined. There was an altar very close-by.

There’s no way to sum up the complex ruins and the history of this place, so I have chosen merely three images and stories. Have no fear, I have hundreds of photos from today (you just wait!). I discovered that the lowest place (TODAY) in the Forum area is at the SE corner of the original Forum. To the east toward the Colosseum, the terrain rises quite a bit. The Imperial Forae to the north of the core Forum are also low. Otherwise, the terrain rises in all directions, sometimes steeply. I couldn’t quite grasp all this until I walked there today. I’m still processing what to think about that.

Foubert, Lien, 2010. The Palatine Dwelling of the Mater Familias: Houses as Symbolic Space in the Julio-Claudian Period. KLIO 92:65–82.

Stamper, John W., 2008. The Architecture of Roman Temples: The Republic to the Middle Empire. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Posted at 2:59 PM |

Comments Off on Bonanza!