Musings

Usually these little table displays outside restaurants have prepared dishes. This one had a very attractive assortment of produce, plus dried pasta and empty wine bottles. I found it rather the opposite of intended, more what wasn’t and what could be. What I find mysterious is the pepper shaker.

I can’t decide if these are meant mostly as we inside this building honor this image’s meaning, or we offer this for you to honor—or both.

The quote is from the Ave Maria/Hail Mary, Latin version, and the actual lines are Sancta Maria, mater Dei, ora pro nobis peccatoribus, meaning the first and last words are left for you to fill in mentally, I’m guessing. The first one is interesting—Holy Mary reduced to just Mary—assuming the reader knows to assume the holiness…. Removing the last word really changes it from pray for us sinners to pray for us. Of course, if you’re in the Catholic family, you know the phrases, and fill in all the words and sentiments without even thinking. Still, removing “sinners” offers a different slant.

The sign reads “Stampa Digitale Antinfortunistica.” I don’t even want to decode it. Points to anyone who puts Antinfortunistica in their business name.

However, I couldn’t resist making Google Translate to flex its muscles; not much of a flex, it turns out. Antinfortunistica means safety, and the whole thing is Digital Printing Safety. I liked it better when I didn’t know….

Posted at 10:22 PM |

1 Comment »

Yeah, it’s one massive ruin.

Spectators did not experience the interior of the Flavian Amphitheatre as anything like this. There was finish—cladding (mostly travertine) on the walls, staircases and access archways, statuary to remind visitors of gods and men (and probably goddesses and women), and most of the surface you see here was really seating, aisles, and arched entries. There was a cloth shade-cover that could be unfurled. So, no, it didn’t look like this. It’s like a skeleton compared to a living body. (Sorta.)

Drawing from several sources, this is what I conclude…. Spectators entered for free with tickets specifying a seating area, and some events lasted for days. The inauguration, in AD 80, lasted for 100 days, and later the stage area was modified so it could be flooded and used for nautical battles. A typical spectacle began with a morning opening parade (pompa), followed by fights between wild animals, hunts by armed men of animals, and shows of tamed animals. The experience of the latter was augmented by stunning scenes of their wild habitats. There was a break midday, used for executions. The goriest were damnatio ad bestias, in which the condemned were torn apart by wild animals. There’s no evidence that Christians were punished here in this manner. Between the major events, people played gambling games and postured to impress. [I tried a vertical panorama, an experiment; since the camera/phone can tell what’s “up” I didn’t know if it’d work—it did! The distortion is interesting, bowing the very vertical walls.]

Regarding the spectacles in the Colosseum, Claridge (2010:317–318) notes:

Gladiatorial shows were called munera (dutiful gifts) and were always given by individuals, not by the State. By the time the Colosseum was built they were being held as a regular public event, in December, as part of the New Year ritual, coinciding with the yearly political cycle, when they would be paid for by the incoming magistrates. At other times they could accompany the funerary rites for major public figures, or could be held on the anniversaries of past deaths. They were also staged in celebration of military triumphs. Such was their popularity that from the reign of Domitian it was decreed that in Rome they could only be given by the emperor; and elsewhere they required his sanction. The daily programme was usually divided into three parts: wild animal hunts (venationes) in the morning, public executions at midday, and gladiatorial contests in the afternoon; shows could run for many days depending on the available number of animals and gladiators. Trajan is said to have celebrated his Dacian triumph in AD 107 with 11,000 animals and 10,000 gladiators in the course of 123 days. Gladiators were a mixture of condemned criminals and prisoners of war (who were generally expendable), and career professionals (slaves, freedmen, or free volunteers), mostly men but occasionally women, specialized in different types of armour and weaponry: the heavily armed Myrmillo (named after the fish on his helmet) and the Samnite both had large oblong shields and swords; the more lightly armed Thracian, a round shield and curved scimitar; the Retiarius only a net and a trident. Others fought from chariots (essedarii), or on horseback. The fights were often staged in elaborate sets, with movable trees and buildings; the executions might involve complicated machinery and torture; some acted out particularly gruesome episodes from Greek or Roman mythology. Animals for the venationes came mainly from Africa and might include rhinoceros, hippos, elephants, and giraffes, as well as lions, panthers, leopards, crocodiles, and ostriches.

An observation: Romans use rear balconies like back porches, for storage and not-quite-so-public activities. Of course, it hosts plenty of drying laundry, plus often hot-water heaters are on the walls, piping the hot water inside—they’re the boxes on the walls. Here’s what I’ve been chuckling about: people store ladders there. Apparently, with high ceilings, people need ladders once in a while, and there is no “ladder for the building” or ladder that can be rented out from a nearby business. So many apartments have a ladder, and the place to store it is on the rear balcony (there’s one above the gate leaning next to the water heater).

An hour on a Friday afternoon…: we took a break using seating framing the church entry area part of the Piazza in front of the Chiesa di San Salvatore in Lauro, north of where we used to stay. We discovered several things. We saw two nursing moms take a break down from us on the same seating, each to feed their young-un while Pops idly stood by the stroller. No modesty cloths, just doing what needs doing. We also enjoyed the children playing out front, hopscotch and a bit of soccer-ball footwork. Then, at 5:30, the church bells began pealing, and Friday evening mass got underway. Music emanated. The kids kept playing. Then, just before 6, a procession formed in the doorway to the left of the church door. In the front were fully adult men carrying the cross and I don’t know what else—they make altar “boys” old here…. The group emerged and made a loop into the church, with the somewhat tottering highest-ranking fellow (judging by the tall headdress) at the end with two flanking attendees. No one told the little boy to stop and pick up his soccer ball, but he did. He was much more focused on the ritual than the group of girls. What you don’t see is that two of the nannies watching the kids looked like middle-aged Filapina ladies. Behind the officials, several toursts surged in, drawn by the pomp. We kept sitting and watching.

Claridge, Amanda, 2010. Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Posted at 4:35 PM |

2 Comments »

I scored. Thanks to my fine husband for being so game and for making it happen.

Yesterday was Ostia; today was…the Palatine Hill and Rome’s Forum!!! Actually, we saw a huge civic-ceremonial center, elite domestic compounds, roads and alleys, and some commercial activity areas.

The sun angle/intensity makes it seem like we were out there after dark, but no. This is the famous Aedes Saturnus, or Temple of Saturn. This version dates to AD 283, and is at least the third incarnation of a structure honoring this deity in this location. The first was back in the times of the earliest ceremonial buildings, traditionally considered the 5th C BC.

This building housed the city’s treasury, maintained by elected public officials called quaestors. Notes Stamper (2008:37):

Because Rome’s economy was based on agricultural production, such a temple dedicated to the cycle of the seasons and the growing and harvesting of crops was important. The notion of divine embodiment in the seasonal death and rebirth was essential to the agrarian culture, a tradition that related to Demeter in the Greek world, the primary divinity associated with crops. A statue of Saturn that stood inside the cella was wrapped with woolen bonds which were undone of the day of the feast, December 17, an event that

included a ceremonial sacrifice, with senators and knights dressed in togas, and a banquet that ended with the chant “Io Saturnalia.” Like the feast day of Jupiter, it was a day of festive gaiety, with shops, schools, and law courts closed, an event that became a yearly holiday. Ceremony, festivity, honor, and gaiety all became distinguishing features of the events surrounding the cult temples. Although none matched the importance of the events associated with the cult of Jupiter, they nevertheless imitated their style and intensity of spirit, becoming a defining characteristic of Roman culture.

With the line of standing columns, the eye is drawn to this ruin in the immediate area of the core of the Forum. It faced the Comitium, where the senate made decisions about the funds held in the Temple. It had three adjacent cellae, and was accessed via a long flight of stairs (now gone), as the floor was on an unusually high podium. Only parts of the front portico, with eight columns and part of the pediment, still stand. The surviving columns are of stone of many types, robbed from different structures. This recycling process is called spolia. The remaining portion of the architrave shows a frieze of acanthus leaves and palmettes; it dates to about 30 BC, and probably was salvaged from the burned, second version of the temple.

This is the lower peristyle garden (open courtyard within the compound) of the Domus Augustus, which drapes across the southeastern Palatine Hill. The upper peristyle garden contains a hexagon pattern, in a shallow hardscape design. This one is to the south and east of the upper one, and at least 5 meters below it (my guess). The hardscaping is a bit more 3D, and the blue flowers really make it pop. The complex is immense, and dates to AD 92. Augustus himself was said to inhabit the same bedroom for more than four decades, so I don’t know what his household did with the rest of the vast square footage of the Domus complex.

Originally, when, as a younger man known as Octavian, he moved to the Palatine and began construction, his house originally was designed in an unusual way resembling those of Hellenistic dynasties, with two courtyards and public and private zones. However, Octavian stopped construction, struck, it is reported, by a thunderbolt from Apollo, and had that structure razed. Upon the rubble a new construction begun that was three times the size (where did he get the area—by reducing gardens? razing other structures?). The new complex was over 22,000 m2 (over 5.4 ac), had a domus publica and a private area combined to make the Domus Augusti. It had a curia, two libraries, a porch supported by one hundred columns and decorated with statues of mythical Danaids, and a giant terraced wing to connect it with the Circus Maximus. The latter allowed him to process to his viewing area without mingling with the crowds.

He had a temple to Apollo to his complex, further increasing the symbolic weight of his complex. Notes Foubert (2010:67–68):

From the ancient sources it clearly appears that Augustus also attributed an important role to his wife in the elevation of his residence from the private to the public sphere. Suetonius states that Augustus presented his house as a stage of matronal display, claiming that the clothes he wore were hand-made by Livia and his daughter and granddaughters, thus associating them with one of the activities par excellence of an ideal Roman matrona. Her role as a supervising mater familias in the upbringing of several children living with her in the Augustan residence confirmed her role as an exemplary matron. It is known that Caligula and Claudius, among others, spent their childhood under Livia’s care and that other imperial children had received teachers from Livia’s household staff. These examples clearly show that until his death Augustus deliberately attempted to create a lieu de mémoire on the Palatine and that he believed that Livia had her role to play.

Other than the vast scale of this complex, it’s hard to even guess at the rest while strolling the dusty walkways where the public is allowed to venture. I could not guess at the function of most of the enclosed space, beyond the desire to impress.

To go a different direction, there are small features across this area of great importance, or at least being the physical embodiment linked to complex tales. That circular feature centered behind the center pair of poles is called the Lacus Curtius. It’s actually within the actual limits of the ancient Forum; a much larger area is typically termed “The Forum” today. The Lacus Curtius is an ancient feature of the Forum, and like others ancient constructions here, its original form and symbolism are now unknown. Livy gives an early story about this feature, in which the Lacus Curtius was the original pool/swamp here. Plutarch describes it as very muddy, enough to trap a horse. Varro wrote that it was consecrated in 445 BC. Titus Livius described it as a deep chasm amidst the Forum, which was reputed to never to be filled, unless by Rome’s most precious thing. A young knight, Marcus Curtius, the legend goes, then rode his horse into the abyss in sacrifice, to remedy this. A marble bas-relief portraying this scene was discovered nearby in 1553.

This area was excavated in April 1903 by workers directed by Giacomo Boni (whose grave is atop the Palatine). The Lacus has two layers of base slabs topped by a travertine layer surrounded by a curb. It had a parapet wall to set it off, set into pits remaining in the curb. The shape is now trapezoidal, and its form in Caesarian times and before is undetermined. There was an altar very close-by.

There’s no way to sum up the complex ruins and the history of this place, so I have chosen merely three images and stories. Have no fear, I have hundreds of photos from today (you just wait!). I discovered that the lowest place (TODAY) in the Forum area is at the SE corner of the original Forum. To the east toward the Colosseum, the terrain rises quite a bit. The Imperial Forae to the north of the core Forum are also low. Otherwise, the terrain rises in all directions, sometimes steeply. I couldn’t quite grasp all this until I walked there today. I’m still processing what to think about that.

Foubert, Lien, 2010. The Palatine Dwelling of the Mater Familias: Houses as Symbolic Space in the Julio-Claudian Period. KLIO 92:65–82.

Stamper, John W., 2008. The Architecture of Roman Temples: The Republic to the Middle Empire. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Posted at 2:59 PM |

Comments Off on Bonanza!

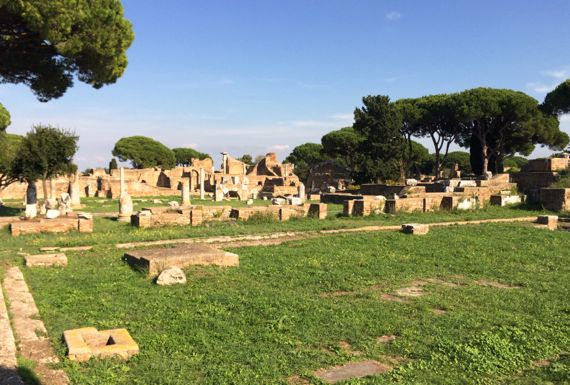

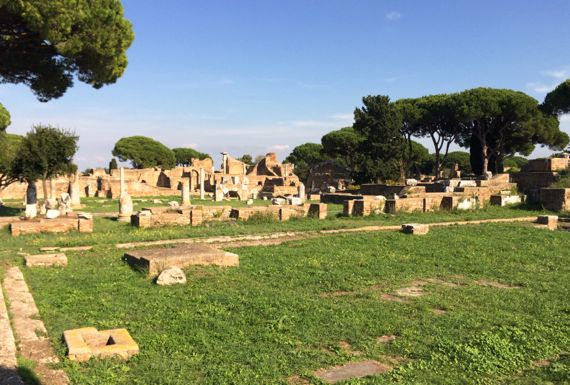

Many options for the day: I chose a day-trip via train/foot to the ex-mouth of the River Tiber, to ancient Rome’s port-town, Ostia. It’s huge. Thankfully, some curators planted pines that are now quite lofty along main avenues, so the sun wasn’t quite as wicked as it might have been. Plus, even 3km inland as it is today, we enjoyed sea-breezes, at least if we weren’t between blocking walls. And there were lots of walls.

The city ruins just keep going and going. Some of the buildings are massive. Far more walls enclosed small workshops, living spaces, and other rooms and passageways. The city-plan is regular, and the main avenues are long and wide. This view is down the Decumanus Maximus (main east-west street, coming from Rome and entering Ostia through the Porta Romana) from near the split at the west end. My info says that the maximum population here was 50K (or 100K; sources vary…).

This view is across a corner of the forum, which is not huge, and into the wall ruins nearby. The edge of the forum is that line of stones across the mid-ground.

Turning the other way, to the left, you see a massive temple with high walls on a very high platform. For scale, two people are standing in the shadow next to the column stub at the top of the steps.

For another bit of the huge-scale of some spaces in Ostia, this is the central open area of a warehouse (horrea), perhaps the largest one of several, but, geeze, the enclosed area was immense. Probably a lot of grain storage. One sign nearby indicated that Ostians ground wheat and made bread here, then sent it up to Rome. If true (how can they tell? records?), then that would save Rome some firewood. BTW, that orange thing surrounds a lone column that is trying to collapse. Those columns are nearly 2ft in diameter. Much of the wheat came from fields in Egypt, removed from the ships at Pozzuoli, the port next to Naples, then transported on smaller ships to Ostia, then even smaller vessels upriver to Rome. Such a shipping model meant many busy stevedores….

Okay, one last huge building, or not-so-huge, just…symmetrical. The theatre. Great form. This is looking across the stage area. Probably there was no stage-wall, so the action happened in front of the row of columns relative to the audience. A temple on an elevated platform is behind where I stood to take this photo…probably a fine backdrop for theatrical doin’s.

The ruins are almost entirely brick/mortar; the facing stone (mostly marble) was removed during the Baroque period and reused on Roman palazzi. Ostia’s harbor became silted in such that the Romans built new boat basins and docks/warehouses in around the new port town, Portus (clever with language, those Romans were!). [See map here from the Italian WikiPee Portus page.] Read more on the city’s history on this fine website/webpage.

Time to go open the prosecco that’s chilling in the fridge….

Posted at 2:18 PM |

Comments Off on Empty city

Three bridges.

Let me decode this photo. It’s taken from the west end of the Ponte Palatino, looking slightly northwest, then north, and finally east—a pano, hence the strange distortion. On the left, the bridge from the west bank of the Tiber to Isola Tiberina (Rome’s island), the Ponte Cestio. On the far right, the bridge I’m standing on, the Ponte Palatino. And next to the latter, also far right, is a single arch that remains of the ancient Romans’ Pons Aemilius, now lovingly nicknamed the Ponte Rotto, broken bridge.

For me, the Aemilius is the most interesting; core parts of the ruin, sources assure me, date to the 2nd C BC. The last updates came in the 1500s. The final insult came in 1887 when one end was removed to install the Ponte Palatino.

Construction of a bridge to this bank from the island was intentionally delayed by the Romans for centuries, we are told. While they long had a bridge from “their” side (the east/south side), the Ponte Cestio, anciently the Pons Cestius, was not built until about a century after the Aemilius (if I have it right). Thus, crossing the river using the island as a stepping stone was not prioritized, although we are told ancient Rome’s location was important as a crossing spot. It was or it wasn’t. Or, it was, but they didn’t want to make it too easy, as enemies and marauders lived to the northwest.

In the late 1800s, when the Tiber was channelized and walled in, with retaining levees built, they widened this part next to the island, I think to force more of the water on this side(?), and the ancient bridge wasn’t long enough any more, so, geeze, it was just an Ancient Roman Structure, so The City’s Wisemen ordered it replaced.

Enough about bridges. Here is a particularly comely city entrance, the Porta Portese. This was roughly the location of the former Porta Portuense. Both names refer to Rome’s port at the river mouth, and the road to there along this bank of the Tiber. The river-mouth was early important as a salt-producing zone, and major trade routes went inland from the sea flats on both sides of the Tiber, as well and up and down the coast. Later, this became a major port area, serving Rome and inland. Major engineering modifications kept it useful (e.g., the massive six-sided basin constructed under Hadrian’s watch and now just south of the airport—see satellite images).

Two other bits to note. We found this sign on the wall of a particularly narrow alley—about one wide shoulder-width at one end—in the original neighborhood of Trastevere (meaning: across the Tiber), south of the Isola Tiberina. Today we first visited that area, and discovered that although unfailingly described as charming and old-world in guides, it is a tourist mecca, and thus a mecca for sidewalk salespeople of all stripes, and not quite an incubator of Roman life as lived by present-day Romans. As to unofficial the English sign, I love its formal design….

Now a bit of action. We also saw a speed-trap setup with four cop cars earlier in the day, with someone getting a ticket and not looking happy about it. Plus, right after we saw this towing (love that lift! a bar on each side of the front tires, spanned together—up and away), we saw another tow truck ready to pull out all loaded up a block away. Since these three aren’t far apart, I guess the cops were targeting this area today. ??

Posted at 10:22 PM |

Comments Off on City life

Google Earth satellite view of Monte Testaccio. From left to right, the arrows point to: ruins preserved in modern market; stacked sherd terraces near closed entrance to the summit; clubs along the west side; and, the stylized amphora fountain.

About 2km southwest of Rome’s historic Forum square is Monte Testaccio, alternatively Monte dei Cocci. It is a mountain of potsherds—at least in near-floodplain, it’s a mountain; elsewhere it would be a respectable hill. The variant names come from testae meaning fragment (and thus sherd in the case of pottery) in Latin vs cocci meaning potsherd in Italian.

And that is what it is: a giant pile of broken thick-walled potsherds. It has a circumference of nearly a kilometer (0.6 mi) and stands 35m (115 ft) high (usually reported as 50m). It has the remains of an estimated 53 million amphorae.

Amphorae are, first and foremost, storage and shipping containers. The name is from the Greek and refers to the two handles. Roman amphorae bodies were wheel-thrown and partly dried, then the base, neck, rim, and handles added using coiled clay. Containers with the same basic shape and purpose were made without handles across Eurasia. Amphorae are known from the Levantine coast dating to 3500 BC (the Neolithic). During the succeeding Bronze and Iron Ages, amphorae use spread around the Mediterranean. The form of amphorae are optimized for safely containing liquids.

Parts of Monte Testaccio were deliberately engineered with retaining walls made of amphorae filled with fragments, and interior fill of amphorae fragments that had been dusted with lime undoubtedly added to reduce odor. Excavations have revealed slips and collapses indicating the pile wasn’t always stable. Researchers have also discovered dumping platforms, which would have made pile-creation more efficient.

Archaeologists have mapped the zones of deposit identified by age of the sherds (generalized)—dates can be ascertained to the exact year, in many cases (so very rare in archaeology!). The oldest sherds that have been found date to ~30 BC. They are from the northern side of the pile, closest to the city’s original port area. As the city spread out, the dock/port area was moved downstream a bit, to adjacent to the Monte Testaccio location. Excavation data indicate that workmen first created a tall mountain, then spread it to the west (toward the river) in stepped vertical layers (platforms). The pile undoubtedly was higher than it is today in its last years of active use.

Most of the amphorae can be identified by stamps put on each vessel while the clay was still damp; they came from only a few places. By far the most common type of amphorae came from the Roman province of Hispania Baetica, from production areas in a small zone mostly along the central Guadalquivir River. Mireille Corbier (2005:418) says farmers transported the oil in skins on mule-back to the Baetica collection area, where it was transferred into the amphorae. Then, it was “taken by boat down the river as far as Seville, and finally loaded onto sea-going vessels to continue its journey from Seville. All of these operations are carried out in the spring, the season when the rivers are high and the sea ‘open’ to traffic.”

They’ve cleaned up the presentation of sherd-layers on the northeast “corner,” by the locked gate to the steps to the top. Once a catholic pilgrimage site with stations of the cross set up, the top of Potsherd Mountain is now usually closed. I think these are artful stacks of sherds comprising these careful terraces, and not how the interior of the mountain actually looks.

At some point, enterprising residents dug wine cellars and other storage spaces into the sides of the mountain. Many on the east side are now clubs, and quiet when we passed by at mid-day.

North of the current mountain is a new market that replaces the nearby market area that survived for on the order of a century. In the center of the new market, architects left a hole in the roof and the floor that allows views of the sherd-strew horizon that is below the market. This indicates to me that the sherd dump was larger than just the mountain we see today.

This giant sherd-dump indicates just how much olive oil and wine came into the city, for hundreds of years. A lot of effort went into making the amphorae and their contents and moving them to Rome. The contents were transferred to smaller, lighter containers (I assume), then transported into the city, leaving dockworkers and warehouse managers with TONS of amphorae that, poof!, they had no use for.

Corbier, Mireille, 2005. Coinage, Society and Economy. In The Crisis of Empire, A.D. 193–337, edited by Alan K. Bowman, Peter Garnsey, and Averil Cameron, pp. 393–439. The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. 12. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Posted at 10:41 AM |

1 Comment »

Late yesterday, I got whammied by a bad cold. Sniff, blow; repeat. I managed to get plenty of sleep, thankfully, but I spent the day an energy-less lump.

The Great and Wonderful Guru went out for supplies, and discovered the nearby street was a forest of vendors, mostly of used clothing, heavily attended by locals, along with a few tourists. He came back with a fine grocery assortment, including a Bob’s Red Mill soup mixture, an Italian version called zuppa di farro. It has split green peas, lentils, and farro. I found a deep pot (kitchen has a good assortment of tools), loaded it with water and some of the soup mixture, and set it to boil. I figured 50 mins of simmering, and that was about right.

Farro is a type of wheat (Triticum spp.), and WikiPee notes botanical and common names do not always match up. The ones in this soup mixture are longer like “regular” wheat, not stubby like barley. This soup mixture would have been customary to ancient Romans, and peoples of the Levant.

By day’s end, I felt on the mend—fingers crossed.

Posted at 10:22 PM |

2 Comments »

With our luggage, we made one last tour of the end of the pier so I could check for fishes. The “black ones” that school high in the water were there, along with the larger silvery ones that hang deeper, and a few of the skinny small ones (not in photo) that may actually be anchovies.

And now I know why. As we stood there, a local fisher-dude came by with his rod and a bucket, and put them down at the south end, closer to the rocks. Then he snagged a paper sack that he had in the bucket…and starting throwing bread into the water. Well, that’s how you get the fishes’ attention!

With regret, we headed up to the station and began our train journey, which took us mile after kilometer down the coast, which we should have expected and didn’t (I think since we arrived in 5Terre via Florence, and thus via an inland route). So, at least through the trees/palms, we saw the sea all the way down until we turned inland toward Rome near its airport.

As it happened, we passed through the station we wanted to disembark at, but our express train didn’t stop (and we didn’t expect it to). So, we had to find the regional train (effectively a local for our purposes) to double back. The connection was tight and we couldn’t find an open ticket booth near our track, so we took a deep breath and did the Italian (not merely Roman, surely) thing, and just boarded.

Without being interviewed by an official en route, we disembarked at the third station, in a splash of low-angle sunlight, and walked the few blocks to our new home. I wonder how many people who got off at the same station also did not have tickets. (We have heard stories of the expensive perils of not having a ticket, or a validated ticket…and we feel VERY FORTUNATE!)

We hooked up with our new host’s nephew, who has excellent English, thankfully, and got the run-down on this and that (how the key needs to be joggled to enter the outside door, how the windows open/close, and the one that took a while: how to get on the internet). We now have a balcony that looks into a tree! More luck!

Posted at 2:20 PM |

Comments Off on We are lucky

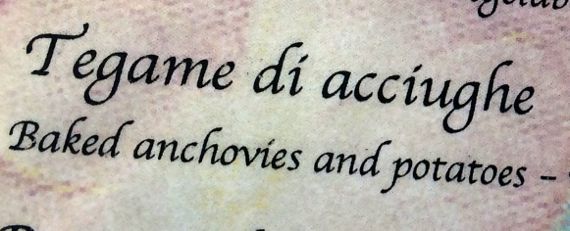

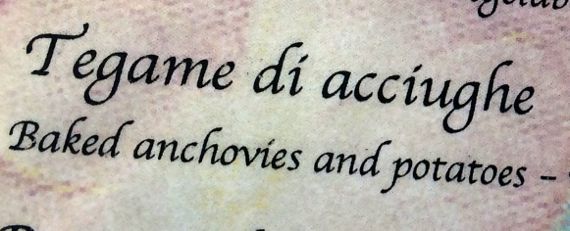

Is there a clamoring out there for FOOD shots/info/stories?

Okay…a tidbit, an appetizer, you might say. Here on the Liguria coast, one specialty is Tegame, which is a stew/roasted dish of potatoes and anchovies (fresh, mind you), along with tomatoes.

The fish is nothing like anchovies from a can, and quite tasty. (The appetizer version of anchovies with lemon, whew!, very fine!)

I’ve had Tegame from three different restaurants here in Vernazza, and the version pictured is from Trattoria da Sandro (the name varies), up the street from the harbor-square. It is the most carefully formed and stacked of the trio. Potato slices are on the bottom, several layers deep, then the anchovy layer, then tomato slices. Every version is yummy, and I couldn’t pick one as better than the other two; they are just a spectrum.

Today we were bold. We hiked from here to Corneglia (not to be confused with Cornelia, Gee-Ay, although the pronunciation is very, very similar). The route was very up, from sea level here at Vernazza to a high point of 207m, if the sign was right. Since the up and down are not singular, there’s a bit of excess and repeated up/down, so the gained elevation far exceeded 207m…at least that’s the way it felt.

This was the first true trail-day for my Cascadias, which I purchased on the repeated recommendations of my social media friends who’ve recently hiked the AT, PCT, and other fine trails in the USofA.

The CinqueTerre trail materials we saw said to expect to take 1.25 hrs to do the 3.5 km from here to Corneglia. We took breaks, and it took us 3 hrs, maybe a bit more. We may have been slow, but the printed recommendation is shorter than I bet the young hoofers that passed us traversed it. Few of the people we saw made it in that span, I am certain. And, we don’t even know if the 3.5 km distance is close to correct…. Not whining, we had a fine time, and were in the cool morning shadow for much of the trail coming out of Vernazza, which was very very pleasant, despite the elevation gain (pant pant).

Posted at 3:43 PM |

Comments Off on (Cupping palm to ear)

We got our hiking tickets or park-entry permits so that we could leave the town and explore, just a wee bit, the foot-trails for which this area is famous. Actually, we set out on one trail, which took us high above Vernazza, and among the agricultural terraces I’ve been admiring from below. A few terraces had kitchen-gardens, with tomatoes, peppers, and other vegg, plus crops like olives and grapes. Among the rocks stacked (not mortared) to make the retaining walls, I often saw oregano, or perhaps its cousin marjoram (not sure I can distinguish; both are Origanum spp.). I do not know how old the terraces are, but many are currently being maintained.

Extending quite a distance up and around the hill is a single-rail tram(?), rather like a motorized wheelbarrow that can deal with the steep slope. For a bit, its rail followed the foot-path we traversed.

The tram-rail vehicle is quite something, with a motor, seat, and cargo containers that are like trailer-carts bringing up the rear (if going uphill). Personally, I prefer the trails; riding that thing looks just plain…scary.

For another sense of popular activities here, Vernazza’s harbor-side is a popular place for Asian women in fancy dresses to get their pictures taken with their fella. Or that’s what we assume. Not all are in white, like this lady; we saw one in a fuchsia dress.

Almost forgot to mention that this morning when we checked the harbor before we sat down to b’fast, we several schools of fish both in the harbor (also sea urchins) and along the pier where the taxi-shuttles pull up for passengers to debark and climb on. Down on the bottom a kindly local fellow pointed out a barracuda, long and skinny, on patrol we thought but not apparently on the hunt. FEESH!

Posted at 4:35 PM |

Comments Off on The hills are…steep