Musings

As we drove along this small estuary, we decided to stop and behold it…get a bit more closeup, at a well-placed pull-off. And to set foot in Cornwall for the first time on this trip. We parked, and as we began strolling down to the waterfront area, I saw Army Men. Real, not an art installation in the shrubbery.

Three guys, in camo, with helmets and guns (pretty sure) and daubs of drab on their faces. Right in the vista-view pullout.

We spoke the more casual but still uniformed guys down by the water (no helmets or face-paint), and they said, training exercise. While we were in the general area, we saw two large helicopters also. Maneuvers, is that the term?

We made our way to Rame Head, one of many end-of-the-road peninsulas. Windy and sunny. On the high ground behind me is an installation now used by volunteers to monitor activities on the coast, and especially radio traffic for SOSs. I assume many are retired military. They had a telescope and binocs. Couldn’t see the radios.

We stopped in Polkerro for a stroll about town. The Pol- part means pool. We had crossed the Tamar River into Cornwall before the Army Men, and Polkerro is a tourist stop rather than much of a fishing village any more, so many shops had Cornish this and that. On our way out, we succumbed and got hot pasties to go; I had chicken and leek. Yum.

Polkerro harbor. Mighty rusty, the pulleys and whatnot on those fishing boats to the right.

Our daily castle: Restormel. Near the once-stannary town of Lostwithiel. I mention this because stannary is a new vocab word for me—means that the community was a center for monitoring the production of tin, so the royals could get their cut, I assume, and also possibly for minting coins.

This the gate looking out—two gates originally. The second shows the inside of the castle, same direction, from the upper walkway.

This is the administrative heart of the Duchy of Cornwall, and we all know who the Duke is, roight?

Posted at 10:22 PM |

Comments Off on Welcome to Cornwall

We “did” more than Dartmoor, but Dartmoor was a highlight. And we didn’t “do” Dartmoor; we just cut through a slice of it. This part was remarkable for the narrow two-way roads, deeply incised into the terrain, with poor visibility very far ahead to spot oncoming traffique.

There are Dartmoor ponies. I don’t know if this is one. It looks rather like a pony, and not a horse. And we saw it on Dartmoor. Conclusions are up to you.

We set off walking on a route I had charted from afar, and quickly realized that we needed to turn back. This lovely forest primeval is just a pine plantation on moor-steroids, meaning that you walk on soft ground, wet in some places. It is not unlike walking on moist sand, requiring a LOT of energy…so we turned back. That’s adventure.

This is called a clapper bridge, and is in Postbridge in the center of Dartmoor. Clapper bridges are stone slabs on a line of piers that cross a river, often near a ford. Interesting conjunction. (If WikiPee is right.) They are essentially Medieval…. We visited this bridge in 1989 during our honeymoon….

Stone alignments on western Dartmoor…. One of these fellows told us that this pair of stone alignments are 87cm apart, and align with the rising of the Pleiades in 1600BC. There are actually two pairs of Pleiades alignments here, with the other ever so slightly differently oriented, which he said fit with 2000BC. We also saw a stone circle and individual standing stones, and more. Plus what they call “hut circles,” which could have been circular foundations for low-walled buildings. Or for cattle pens. I have seen no excavation data and soil testing on these constructed features.

The rocky tops of the rounded crests of Dartmoor “peaks” are called tors. My dictionary notes: “Old English torr, perhaps of Celtic origin and related to Welsh tor ‘belly’ and Scottish Gaelic tòrr ‘bulging hill.’” If this were on a hill it would be a tor, but it is next to an abandoned WWII airfield called Harrowbeer.

Posted at 4:07 PM |

Comments Off on Dartmoor day

Looking up at the west entrance to Badbury Rings hill fort. These tend to have begun as Neolithic enclosures, later modified into Iron Age ring/hill forts. This entrance has several rows of deep ditches/high berms to control access or impress non-locals.

Its wildflowers are these little yellow ones.

Street view, Dorchester.

Homemade parking lot sandwich: cheddar and rocket on a stale bun. Mmmmm!

Our lunch view: the giant Maiden Castle, similar history to above, with even more complex berm-ditch entry area (west end). Note grazing sheep.

Sheep are an easy way to maintain these grassy archaeological pastures. Twin lambs should make the farmer happy. Dorchester in background.

Archaeologists(?) have revealed this Celtic-Roman temple atop Maiden Castle…the altar is in the far room; these two small rooms (foreground) were where its tender lived; the treasure was here, including a piece of metal with Minerva on it (so, a Minerva temple?). We saw this pattern in Rome, too, where the gelt was kept in separate rooms.

Jurassic cliffs bordering West Bay, aka Broadchurch for you fans of British television. En route, we passed the turn to Chesil Beach, but didn’t take it. Choices, choices.

Small church, West Bay.

DI Hardy’s house, the blue-blue one with the narrow double doors and colorful floats/bumpers, West Bay, just up the river channel from the marina, and behind the bathing gulls.

Blackbury Camp is a much smaller fortification above Sidmouth (mouth of the River Sid, eh?). The late-day light was stunning, with the leaves not yet out.

The most prominent flower here: bluebells. Very Broadchurch, second season.

That’s it for hill forts for a while. Conclusion: with the great ascent of Maiden Castle in the mix, average ring-fort ascent is about 25 Fitbit flights (otherwise, much less, thinks the cynic).

Post-dinner perambulation past fancy waterfront Sidmouth hotels….

Posted at 10:22 PM |

Comments Off on Hillfort-wildflower combos, etc.

We heard rain all night, and into the morning. We’re still on not-quite British time, so I made coffee a bit late. Then we headed downtown to secure a parking space (tricky), and walked to the cathedral to be wowed by the craftsmanship and immense enclosed space, while simultaneously ignoring the awful things the Catholics and their daughter-clan, the Church of England have done.

Without a doubt, the interior space is stunning, all those vaulted arches, the stone imported from afar(?), and carved stone and wood details.

Here’s the ceiling under the spire, which is atop the crossing of the transept. The supporting columns are no longer vertical from the great weight they shoulder. We saw the little tags that the historic preservationists use to monitor small movements (targets for laser-measuring devices).

The quire. I don’t know if singers are a quire also, or a choir.

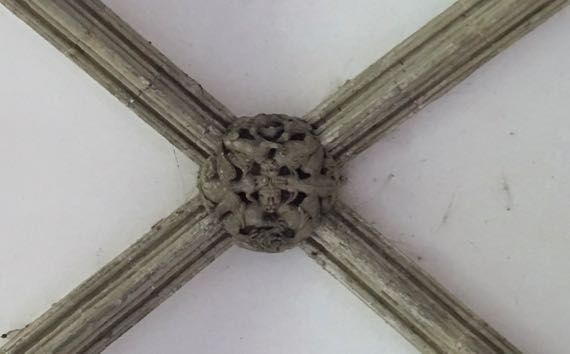

Up near the altar, inserted with access from a side aisle, is a little enclosure, the Chantry Chapel. Here’s a detail of the ceiling. Much of the paint is gone from the rest of the church, so it is a surprise and refreshing here.

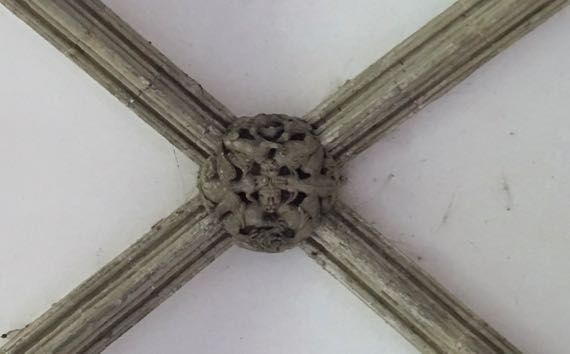

Here’s a detail of life and death tangling on the ceiling above the Cloisters perimeter walkway.

My eyes kept drifting toward this pair of evergreens in the middle of the Cloisters—otherwise there was no attempt at a central garden.

Of course we went in the Chapter House to see the 1215 Magna Carta (one of four), in a little dark room that reminded me of the breast-feeding or milk-expressing pod I saw at the airport in size and lack of windows. This CH is circular, with arm-chair width niches surrounding the room, and a carefully needle-pointed cushion in each. I’m assuming the notables actually perch on them, which seems rather strange to me—as each had the name of a saint (mostly male), with floral details repeated in the surround. This one was for Teresa of Avila, and says “The Way of Perfection.” There’s a potentially hugely stressful approach to life….

Instead of thick stone walls, this Neolithic henge became an Iron Age hill fort, using ditches and a high berm to provide safety. The henge is the central ring-ditch, surrounding the village area, and is specifically a causewayed enclosure (it seems). The later occupants dug a second ditch farther out, and used the fill to create a circular berm, making two ditches. The entrance are to the east and west (not exactly), and the west break in the wall faces Old Sarum exactly. Must be deliberate. It can just be seen in the distance. Must have been the plan. Some speculate that cattle would have been kept nightly in the space between the inner ditch and the berm. (From left to right: outer berm (outer ditch not visible); Iron Age flat area; Neolithic henge ditch—perhaps deepened by later peoples—and inner village area.)

Posted at 3:49 PM |

Comments Off on Architectural security

One thing I hoped we could do on this trip was walk out from Stonehenge, and today I got my wish. It was kinda sunny and pretty darned windy. The ground was damp and no more—not squishy at all. That horizontal grey scar “before” Stonehenge is a employee service center that was under construction last year. Most people who just walk to the stones will not notice it; however, from here: pretty obvious.

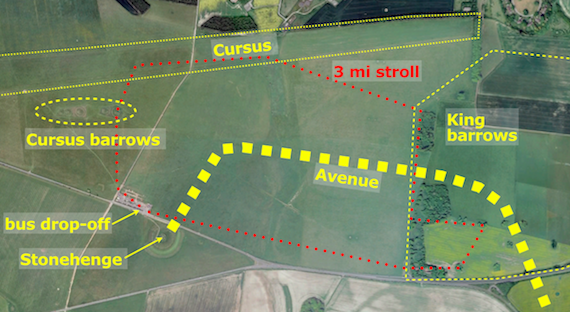

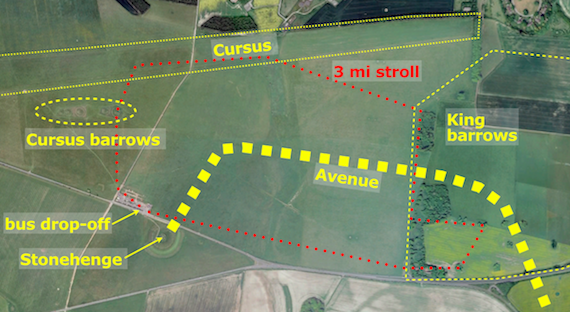

We walked a loop that took us to the Cursus barrow group, then down the Cursus, along the Avenue (very indistinct), into the King barrow group, then back, with a chance to look from the Avenue into Stonehenge (to see that alignment). We walked with the sheep. (And didn’t do that jog to the east in the “yellow” field—shown was the plan, not what we actually did.)

Along the old road next to the King barrows, we admired these gnarly trees. We’ve been admiring gnarly trees this trip, beginning in the grounds around Windsor Castle.

Then we visited the land of the miniatures, aka a model train show.

And the Guru found a “silly” tucked in this field of dairy cattle.

Serendipity can lead to amusing moments like this…we followed a back road that my “nose” thought…unlikely, but GooMaps indicated we could drive through…nope, only foot traffic could cross the river…look what we did find!

Posted at 10:22 PM |

1 Comment »

We were slow this morning, jet-lag slow. On the other hand, we did pretty well after we got going. We returned to downtown, parking above the Boston Tea Party mentioned yesterday, and went straight to the Salisbury Museum. The ambitious crew there has been updating the displays and presentation of the institution, and they are doing a fantastic job. We met two fellows from here last year, and so the SM was tops on our list for this trip. Unfortunately, our friend is away on leave, but he kindly left our names at Reception, so we breezed in. People can be so nice! I loved their new-as-of-2014 Wessex Gallery (of archaeology), and the Guru admired their handling of type and general museum-ing.

This photo is of some fine-quality beakers. Beakers are a vessel form with relatively straight/vertical sides, and often a slightly everted rim. (I think.) The earliest beaker-users in this area also kept domesticated animals, including cattle. This meant they had to do the whole pasture thing, and keep the cattle safe from human and animal marauders, a significant undertaking for the few individuals an extended family or residents of a hamlet. They also grew crops, and used wild foods.

There is another class of artifacts dating back to ancient times, also Bronze Age like the beakers, which I have seen called “precious cups.” They are precious because they are made of very special (meaning unusual/rare) materials, including amber, gold, silver, and these of shale. There are very few precious cups known, and the shape may relate to a general tendency towards what some have characterized as a “drinking culture.”

I didn’t know shale could be worked like this. Note the decorative details inscribed into the surface and handle. Such craftsmanship!

Here’s a detail of a very large vessel, a burial urn (held cremated human remains) with a bi-conical shape. The widest part is the ridge near the bottom of this shot. The size of this ceramic vessel meant its maker(s) knew how to handle clay and firing.

The above all date to the Bronze Age, which obviously was a time of people who used bronze, but they were also adept at crafting, building, wood-working, and making stone tools. Let’s jump forward in time….

There’s a huge and distinctive flat-topped conical landform a few miles north of Salisbury. It had an Iron Age fort atop it, which was supplanted by Romans both atop and around the foot, living in a community they called Sorviodunum…. They had several roads that met near this human-modified landform, so it was an important place. Later peoples added the tippy-top area, making what became in William the Conqueror’s time the king’s castle. This model shows the tower/keep that was the most fortified place within this already fortified place was to the right in the upper, central area. The main entrance was from the left. Residents of the lower tier even built a cathedral-sized cathedral (consecrated in 1092), that huge building what was a typical church/abbey complex in the lower right quarter of this view. It is difficult to gauge the scale of this fortification with just the eye; however, it wasn’t big enough (or something), and movers and shakers set about re-locating the community so that their new cathedral was consecrated in 1220, and the old cathedral dissolved in 1226. Sometimes I mention the abandonment of former important macro-regional centers of political economy—the story of Old Sarum fits neatly into this topic.

Here’s the view from the King’s Castle keep, looking across the flattened remains of the cathedral. Most of the building stone was left at Old Sarum into the 1500s, when official permission was given to take it. Only some foundation stones remain in the upper castle, with upper approximations of the walls made of mortared flint cobbles that had been in the wall-fill, and too small to be of interest to the long-ago stone-takers. The cathedral and buildings of the lower terrace were easier to get to, and they are mostly gone. The outline is only partly existing foundation stubs; the rest have been added in modern times. This area is happily used by dogs and dog-owners; we saw dozens playing and running/walking (dogs/people) as we overlooked the terrace from the remains of the king’s apartments.

Here’s the modern wooden footbridge that crosses the ditch (and what a ditch!) from the east, providing access to the inner, upper castle area. Note how the weather is changing…the bright sky of the previous shot shows grey clouds accumulating. We got back to the car just as the raindrops arrived. The rain didn’t last long, and we had plenty of sun until darkness set in about 8pm. (And there’s now a crescent moon.)

Info on beakers and beaker-making people from the Ashmolean. Details on similar from a Somerset source—Somerset is the next county to the WNW.

Posted at 3:30 PM |

Comments Off on Ancient and merely old (Wiltshire version)

Mahonia spp. I’m used to yellow flowers and blue “fruit,” but this one has yellow fruit.

Yesterday I encountered a word I hadn’t remembered encountering before, but of course I had…and forgotten. The word is carnyx. Synonyms are war trumpet and Celtic horn. Apparently it was ritual instrument used in warfare. Only a very few have been found—and only one in the British Isles: the Deskford carnyx.

I saw that carnyx in a display at the National Museum of Scotland, along with a reconstruction (with a tantalizing red tongue). And I saw the word carnyx in the accompanying explanatory materials.

However, I focused on getting a decent memory-photo (bad reflections), and thought about how big it was—serious mixed media and complex metallurgy techniques, it seemed to me—still does.

The Gundestrup caldron, found in northern Denmark, has a panel showing a trio of carnyx players (Open Commons photo). This helps us know how it was used. Read more on this page by acoustics professor Daniel A. Russell. He also details many of the times illustrator Albert Uderzo used versions of the instrument in the Astérix series.

Holding those tall pipes must have been tricky while walking. The much later, stubbier bagpipes made music-while-marching much easier, I would think.

I’m guessing carnyces fit into the group of instruments that create vibrating columns of air.

Posted at 6:32 PM |

1 Comment »

I got fascinated with archaeological features of Cornwall and figured out how to call up Ordinance Survey maps that note them. Turns out there are standing stones, stone circles, barrows, ring forts, promontory forts, the whole assortment that are known from the Neolithic landscape elsewhere in the British Isles. And beyond. Those Ancient Ones were busy-busy.

Posted at 10:22 PM |

Comments Off on More on Neolithic built environment

More unexpected blooms…pretty darned early to find phlox. Love ’em, though.

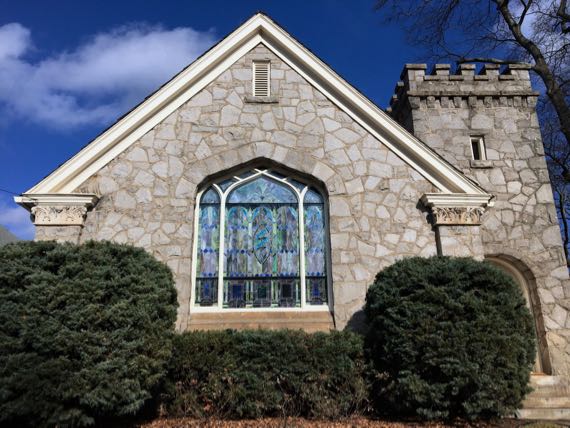

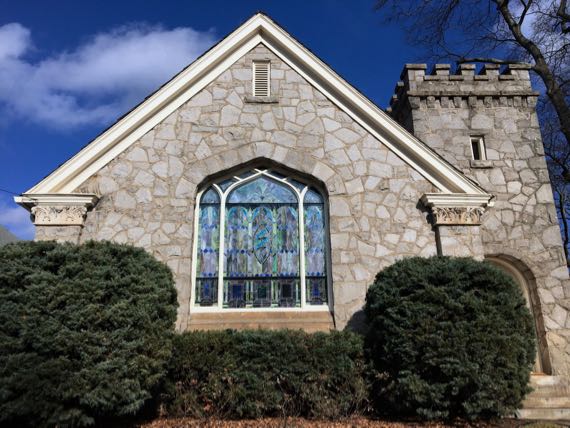

Strolled by this 20th-C church on Degress Avenue just as it was catching the late-day light. Apparently the building is a remodeled house. It’s on the hilltop that was ground zero for the Battle of Atlanta on 22 July 1864, at least in the version portrayed in the Cyclorama (currently being restored at the Atlanta History Center). Love the capitals atop the skeuomorphic (right?) columns that are really small-scale buttresses if you look behind the bushes.

Posted at 5:47 PM |

Comments Off on Sunlit finds

We had sun for a while…in the morning and again in the afternoon…with rain in between. This is from sunny-interlude-number-two. KW, it’s a clematis, right?

Just wanna note that the Egyptian burial pyramids are mostly solid, with very little open space inside (chambers and a few passages); not at all likely to be grain silo-pyramids.

Posted at 8:16 PM |

2 Comments »