Fake mom

Saturday, 28 March 2009

Visited a working sheep farm today, and saw the new crop of lambs and some of the milking process. My conclusion about the shift to pastoralism (from gathering and hunting): you get to deal with a lot of crap.

Saturday, 28 March 2009

Visited a working sheep farm today, and saw the new crop of lambs and some of the milking process. My conclusion about the shift to pastoralism (from gathering and hunting): you get to deal with a lot of crap.

Tuesday, 24 March 2009

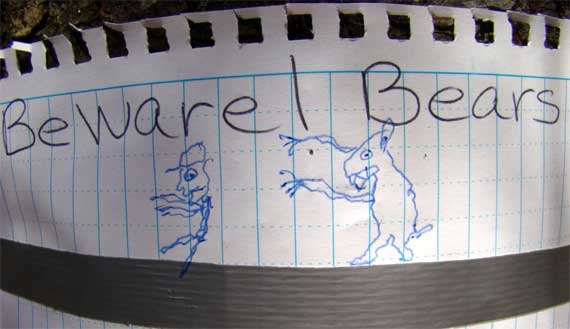

“Beware bears” doesn’t really cover it.*

We’ve been hearing about legislative budget dickering at the Federal level. It’s also happening at the state level here in Georgia.

The legislators seem to employ this logic: cut the heck out of everything, and then wait for the constituent backlash, and use that to decide what “has” to be put back in.

Late afternoon’s breaking news was that the Georgia House has cut the archaeology program to the tune of $279K-plus, including the Federally-mandated State Archaeologist position.

So, the backlash begins. The SGA story is here, and there’s more on the GCPA page here.

Fellow Georgians, please start dialing for dollars….

* Bears are harassing hikers and breaking into their gear along the stretch of the AT we hiked last Friday…. Our companion F added the drawing….

Wednesday, 18 March 2009

This creek drains the Little Park*, and it’s already delivered most of the rainfall from earlier this week downstream. The streambed is dissected, or deep below the adjacent ground surface. This is the result of sediment deposition in the valley, as well as downcutting by the drainage after the forests were removed in the catchment area. So, the pattern you see here is very historic, and relatively recent. The piedmont sure looks a lot different now than it did 500 years ago.

* my term

Thursday, 5 March 2009

Our neighborhood has some lovely old apartment buildings, although some have been condo-ized. These Ionic columns add a delightful detail to the façade of this pair of buildings, which face each other across a lovely garden, a haven in the midst of the city.

Friday, 20 February 2009

First, it was wild land.

Then, the Euroamerican landgrabbers founded Terminus, to be the end of the railroad coming south from Chattanooga. By 1842, it had 30 residents.

Then, Wilson Lumpkin asked that the town be named after his daughter, Martha, rather than himself. Terminus became Marthasville.

And, not long after, the community was incorporated in 1847 as Atlanta.

Then came the War of Northern Aggression, when Union soldiers torched fair Atlanta.

Rising from the flames, residents chose the phoenix as the symbol of the city.

And the reason for this historic recitation*? Over 7–22 March, the Atlanta Preservation Center presents a “Citywide Celebration of Living Landmarks” (buildings, not people). The connection: this is called Phoenix Flies.

I must confess I hear that name and I think of a summer street in postbellum Atlanta strewn with road apples and their attendent clouds of busy insects.

Monday, 9 February 2009

This photo, taken a year ago today, kinda fits my mood: angular and upside-down! Or perhaps this is the architectural version of having your slip showing!Fuzzy would also fit my mood, but not the photo….

BTW, our photo collection shows the camellias were full out this day in 2008. Not this year. Instead, they’re still buds, big ones, but not open yet—at least on our [benchmark!] plant.

Friday, 6 February 2009

The mining company has piled this waste crap (okay, tailings) next to the road in Copperhill, Tennessee. I thought that strange until I got home and looked at GoogleMaps, and I can see that they’re using the pile as a visual buffer, so you can’t see the even uglier mining activities behind it. Clever. I had thought they would prefer not to remind us of the ugly by-products of their surface mining. Apparently, it was the lesser of two evils…. As one county webpage notes:

Copper ore was discovered in this region in the 1820’s.* From the time of this discovery through 1987 the Copper Basin had the largest metal mining operation in the Southeastern United States. Early profiteers gave no attention to the environment, cutting down every available tree for copper smelting, creating an acid rain that killed over 60,000 acres. This turned the land into what was later described as having the appearance of a red moonscape.

So, now most of that hideous moonscape is hidden, mostly by vegetation barriers, but also by being buried. Here, where the highway passes right next to the mine (or smelters, or other machinery—something ugly), they’re “using” the waste piles….

* Not quite; Native Americans knew about the copper deposits before Euroamericans arrived….

Friday, 30 January 2009

Am now reading Kurlansky’s The Story of Salt (2006), which I saw recommended somewhere. I thought it strange when I put the hold on it at the library last week that it was in the Juvenile collection, but I plowed ahead, Explorer that I am. Picked it up today and found out what I could have discovered with a quick google—it’s aimed at the Grade 3–6 set. Still, it’s interesting, although Kurlansky too strongly makes the argument that pre-modern history is based on the salt trade. On the other hand, salt is so cheap and plentiful today that maybe I cannot imagine what it was like “in the old days.”

Friday, 23 January 2009

I pretended to be a Girl Scout today, which made sense since I was at a Girl Scout camp that was empty of scouts. We had the traditional campfire after dark, of course, but since we were really a bunch of archaeologists, we also fired pots in the coals, and avoided dropping toasting marshmallows on the ceramics….

Tuesday, 6 January 2009

Finally, around 3:30 this afternoon, the overcast began to lift and blue skies appear.

Was this to celebrate the third load of laundry of the day? (Geeze, I hope not!) I did them in and around thinking about Mesoamerican archaeoastronomy….