Musings

Flipping through streams, I saw an offering: “Murder in…(English Subtitles).” Seemed darned funny to me.

BTW, picture is from March…lotsa woodgrain, like a relatively soft wood…I’m guessing fast-growing pine, perhaps Southern pine.

Posted at 10:05 PM |

Comments Off on Not a loaf of bread

We found the darkest purple lilacs I remember ever seeing, which we found on the Seul Choix lighthouse grounds.

There’s the light, with the keeper’s home to the left. [Apologies for the exaggerated keystoning.]

It’s on a point that projects out in the M of HOMES.

Contrast that with “our” lake. That’s a round rock (perhaps/probably rounded by humans, and thus an artifact) atop a binnacle. Because of this weighty binnacle that was on/near our beach, that word was part of the vocabulary of the kids who grew up in my generation on this property, and probably would not otherwise have been familiar with the term. Now, why there was a binnacle of this scale here, I do not know, because it’s way too large for a ship/boat on this lake, but not for one a HOMES lake.

Posted at 9:27 PM |

Comments Off on Only choice, plus binnacle

Proof of bridge crossing. Also proof that traffic flowed at 45 mph in two lanes each way, as normal. [Ignore bug smears on windshield and assistant photographer’s quirky focus.]

Ah, we’ve returned to the land of rhubarb. I was taught to pull the stem gently yet forcefully (no tugging) away from the crown (the direction varies from “up”), and I didn’t intend to select a leaf that was nurturing a wee leafette—oops. BTW, the sauce was the strongest pink of the year, almost luminous.

Proof that the lupin remain gorgeous, although somewhat disguised since the grass has shot up to full height, sometimes higher than the lupin.

Posted at 9:35 PM |

Comments Off on Arrival

We went to an art show opening on the main floor of this building, a former overall factory. This is upstairs where the studios, teaching spaces, etc. are. This is one of the latter. The floors are all wood, and creak with such vigor they seem to be expressing something.

Posted at 8:47 PM |

Comments Off on New England through windows

How do you make your state capitol building, here a state house, look more impressive when it has only two stories: put it part way up a hill with a cascade of steps below the main entrance.

Complex tiling patterns in the entry of the public library, Randolph.

Dam and falls in Bethel; mill buildings are to the right.

Exposed interior structure, Howe Covered Bridge.

Orange County Court House, Chelsea.

Oddly, Chelsea has two commons separated by a rushing creek. I spotted this chicken on the bridge connecting the two commons, which of course provoked the question: why did the chicken cross the road? Data based on this chicken is null as it did not cross while I was watching.

We visited several covered bridges along this section of the White River, and this one, Moxley, had an actively used ford just below the bridge, while none of the others did. I figure it’s used by farmers and so on with large equipment.

Cilley Covered Bridge: although the bridge dates to 1883, these boards are from perhaps the last few months.

I’ll spare you any more covered bridge photos; how ’bout some ornamental, um, apples? Guessing…that’s way too dense a flowering pattern not to be an ornamental variety, and I think it’s apple, but I’m no botanist.

Posted at 10:05 PM |

Comments Off on VT architecture miscellany and other miscellany

Flowering plum (?) on dunes.

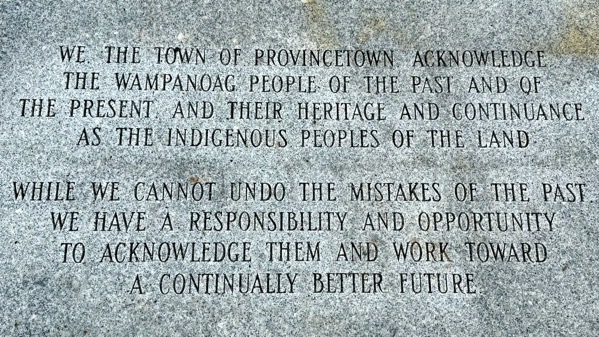

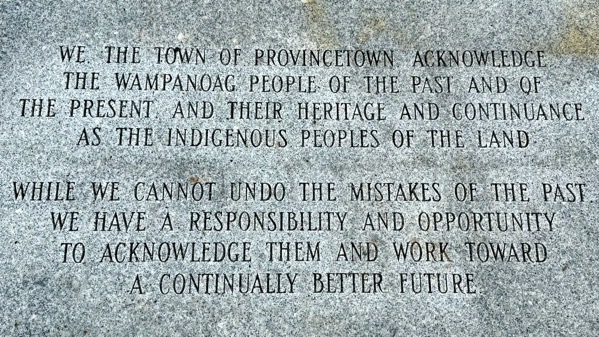

1917 approach, Provincetown memorial.

New plaque, installed around 2010.

The historic main street in Provincetown, dating back to such olden times, is narrow, and now one-way. This section is residential, but most is partly commercial, and no doubt a horror for deliveries.

Tidal flats, very overcast and tide neither in nor out. Saw small crab remains, about 3cm in diameter.

Also, we’ve seen turkeys, one per day the last three days.

Apologies for the late post. I picked the photos, then fell asleep early, trying to fight off the cold (sniff, blow) that came over me Sunday night.

Posted at 10:22 PM |

Comments Off on On Cape Cod

We went through the core business district of Newport, saw looming masts, shops of various sorts, and many tourists. Then, we looped around among the fancy houses, and I mean fancy. However, this is the only photo I took during that entire circuit, and I don’t know who it is…just driving by, ya’know.

I read up a bit on Rhode Island as we drove along, and wondered where that island was, as the state is mostly not-island. Turns out this island, now more commonly called Aquidneck Island, is historically tagged as the island called Rhode, Ile of Rods, or Rhod-Island. BTW, if you can see dots out in the surf, they’re surfers. They only get short rides, but then they don’t have to paddle much to set up again.

Today’s drink I’m sure I never had: a coffee Fribble at Friendly’s (one of the dwindling few still in business). Egads, it was sweet. And huge.

I enjoyed this large knotical display 🤣 🤣 🤣 but you only get to see a few examples.

Technically, the border is more complicated, but this canal is commonly considered to separate Cape Cod from the mainland, which is where I’m standing and the cormorant is posing.

Our late-day adventure was a visit to Nauset Lighthouse, at the beach where The Guru and his fam used to hang. It was relocated in 1996 because coast erosion threatened to topple it. This lighthouse originally stood in a different town from 1877–1923, when it was moved to this area. So this is the third spot for it (I hope I’m making sense 😄; g’night).

Posted at 9:01 PM |

Comments Off on Nautical-ish

Obv, our travel today was on land, yet water was a near-constant companion. We began by heading north on the Jersey side of the Hudson River. Here’s a view south back toward NYC. I think the haze is humidity (ish).

Then we turned east(ish) for the rest of the day. Here’s a swing bridge that crosses the Mill River in New Haven.

We got a fancy lunch, stuffed lobster tail for me and Eggs Benny for the Guru. The Benny was exceptional, and included avocado. My pickled beets side was prepared in a way I’ve never had before, with mustard seeds, then with fresh onions and bay leaf added before serving, and was not very sour/vinegary. The other side is a Cole slaw that may have had a salt treatment to soften the cabbage before dressing.

We also split an egg cream, like we were teenagers on a date. I think I had it once before and thought the same now as then: it tastes like watered-down chocolate milk.

We took a sunset tour of the west side of the mouth of the Connecticut River, not far from our hotel.

We found a pair of swans, keeping their distance, so I have only shots of one at a time. That’s the railroad bridge over the lower Connecticut in the background.

Here’s today’s version of Fort Saybrook; construction began in 1636, directed by Lion Gardiner (1599–1663). Gardiner’s wife Mary Willemsen Deurcant (c. 1601–1665) accompanied him, and their first two (of three) children were born at the fort before his contract ended in 1639. They then moved to what is now called Gardiners Island off the east end of Long Island. The Montaukett sachem/chief Wyandanch (c. 1571–1659) deeded it to him in 1639 independent of the colonies extant at that time. The 6×3 mile island remains in the Gardiner family, whose many descendants include Alexander Graham Bell’s wife, Mabel Gardiner Hubbard.

Next to the fort remains are railroad remains, including this roundhouse. The railroad opened in 1871.

At another stop, we watched the ebbing tide, the clouds, and a few airborne water birds.

Posted at 9:17 PM |

Comments Off on Watery places, lunch

We surfaced in NYC in the Oculus. Here’s the view the length of it, where the eye shape looks far more like two rows of tall, elaborate fencing.

Oculus exterior: these features are to mimic eye-lashes?

Turn around a walk a short ways and you’re amidst the World Trade Center memorial and park area. Here’s the north tower pool with names engraved on panels just exterior to the cascade.

We found the south tower pool dry for maintenance, and almost 100% without spectators, unlike the “wet” pool.

A bit farther along and up a few steps, we revisited this sphere (official name: Große Kugelkaryatide N.Y.), originally between the two towers and damaged on 9/11. We saw it in its temporary location in Battery Park, and wanted to revisit it here.

We walked south along the Hudson. From a distance, this sculpture, called Upper Room, looked like it was surfaced in huge bird seeds. I wonder if anyone plays checkers/chess here.

The fabulous viewing locations for the Statue of Liberty are under construction, so we continued around to the East River, and saw lots of arrivals at the Heliport, including military choppers (perhaps as many as four). They match the black SUVs we saw parked at the Heliport, with plates reading something about Military Affairs and Navy.

If you’re curious about what is under Manhattan streets, here’s a peek…overlapping infrastructure, no?

JCB made special arrangements to see and use this Quantel Paintbox, the magic graphics machine that preceded Photoshop software. Memory lane!

We also ascended to Trinity Church, exploring the graveyard next door.

I enjoyed the decorative details still visible on some of the stones.

Most of the stones are of other materials and far more eroded.

Sunset sky from our room.

Posted at 9:07 PM |

Comments Off on Remembering

We found a high hill overlooking the Susquehanna River. The far bridge is the interstate, but we took the old road, the one showing only two partial spans just a bit closer.

On the hill, we also found the Mason-Dixon trail, and walked it for a few feet.

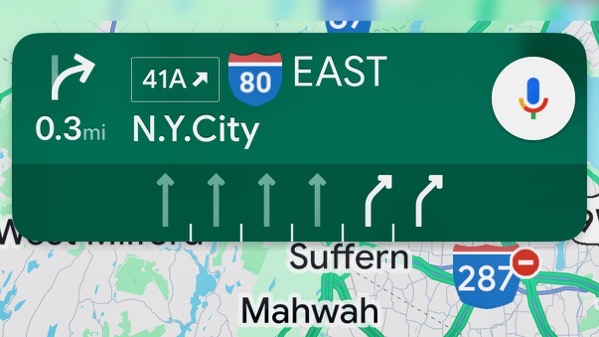

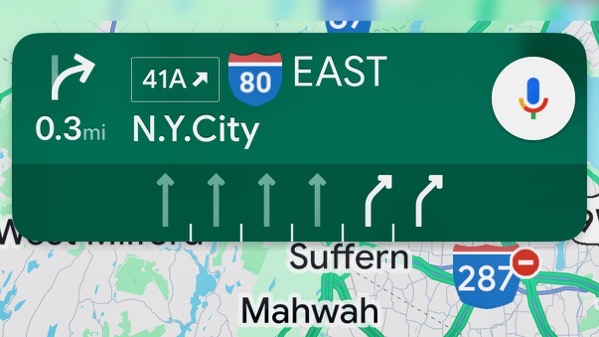

Back on the road, after a short time, our eventual destination popped up on the navigation app.

From our New Jersey hotel parking lot, we can see across the Hudson and into (Upper) Manhattan. We’re staying here because it’s easier to deal with the car (free parking), yet still access the city.

We took a bus across to Port Authority, and walked out of the terminal and, tadah, lookee there! Also, our noses were assailed by a strong whiff of weed-smoke, which turned out to be the common street-perfume of today’s Manhattan.

We walked down to see the Flatiron Building, and discovered it is covered in a layer of scaffolding, and looks bulky and strange.

We also passed by two sides of the Empire State Building. The upper floors look less scruffy than the basal floors.

For a change of pace, here’s a statue of Minerva and two bell-ringers. A Smithsonian webpage says:

A granite niche flanked by pilasters supporting an entablature and attic with clock faces on the north and south sides. Standing in the niche is a figure of Minerva bearing a spear and shield. She has serpents entwined around her arms and breastplate, and she holds her proper right arm out. An owl, whose green eyes used to blink, is perched on top of a bell in front of her. Two bellringing blacksmiths, known as Stuff and Gruff, rotate at the waist and appear to hit the bell with their heavy hammers. Their hammers stop three inches from the bell while a mallet hidden inside a box behind the bell actually strikes the hour.

I thought the owl’s eyes looked odd; now I know why. I’m now slightly sad we didn’t hear the bell toll, but that’s what can happen when you do your research after the fact.

Ah, that’s enough high-points from a brief exploration of Midtown Manhattan….

Posted at 9:49 PM |

Comments Off on Mostly eastbound