Musings

For no logical reason, I present this early digital photo of mine, as a result of which I decided I no longer needed to use the camera’s B&W setting.

Anne was complementary of my vocabulary the other day, but no one would ever do the same of my knowledge of history. Here’re two bits from Patrick Leigh Fermor’s second volume, Between the Woods and the Water, subtitled On Foot to Constantinople from The Hook of Holland: The Middle Danube to the Iron Gates, on his walking trek across Europe that began in 1934. In the first selection, he writes about visiting Vár, the citadel of Buda, above the Danube in present-day Hungary.

Tim [a huge black Alsatian] bounded about among the sarcophagi and broken walls and the ruined amphitheatre and dug for bones in the Temple of the Unconquered Sun; and in the museum we gazed at one of those disturbing bas-reliefs of Mithras in a Phrygian cap, plunging a dagger into the bull’s throat. (The god always wears an expression of unbearable anguish as thought the throat were his own; a hound leaps up to drink the blood and, down below, a furtive scorpion wages scrotal war.) (p.38)

…and…

On the fringe of allegory, dimly perceived through mist and the dust of chronicles, these strangers have an outsize quality about them: something of giants and something of ogres, Goyaesque being towering like Panic amid the swarms that follow one after the other across this wilderness and vanish. No historical details can breathe much life into the Gepids, kinsmen of the Goths who had left the Baltic and settled the region in Roman times; and the Lombards only began to seem real when they move into Italy. (p.52)

I only know one person who I suspect would get all the references in these two excerpts (that would be Pooh, though I may be doing a disservice to Rebecca); I certainly am out of my league!

Fermor writes these bits seemingly without effort, and I realize, reading them, how much knowledge of this and that relating to the modern world has filled to overflowing the places in my brain that, in another day, like early twentieth-century, might have been allocated instead to Classical history.

From elsewhere in Fermor, where is the Istrian peninsula?; what do “cascading pengös�? sound like (Anne?)?; what do crockets on a medieval church’s pinnacles look like?; what kind of garments are “Tintin plus-fours�??; and what’s a “bombinated�? nation-state like?

I must add one last quote, Fermor’s amplification of his assertion that Magyar (Hungarian) is most closely related to the Finnish language.

It was no help, at first, to learn that Magyar, whose resonance is fast, incisive and distinct, is an agglutinative language—the word merely conjures up the sound of mumbling through a mouth full of toffee. It means that the words are never inflected as they are in Europe, and that changes of sense are conveyed by a concatenation of syllables stuck on behind the first; all the vowel sounds imitate their leader, and the invariable ictus on the leading syllable sets up a kind of dactylic or anapaestic canter which, to a new ear, gives Magyar a wild and most unfamiliar ring. (p. 33)

Ictus? Dactylic? Anapaestic? Geeze!

I bet this is right up Leslie’s alley!

Posted at 11:17 PM |

2 Comments »

I often forget just how large New York is—the state!—and how varied its terrain is. We zoomed through the state and city just after Thanksgiving, as you can see from this trip down memory lane. Here’s the view from a peak whose name I’ve forgotten that K and I hiked up to.

Regarding Sunday’s entry, I’ve also added a (crude) map showing where Eagle’s Nest is. That long skinny lake to the northwest is Long Lake, but the one just east of it (and NNE of Eagle’s Nest) has the best name: Fur Farm Lake. Yes, because back in the Old Days a harvesting concern was quartered there. Google’s gotten some bad data, however, because the big lake to the north of these two (no!, not Superior!) is labeled “Camp Seven Alke”. And that last word is a typo for LAKE.

Posted at 10:22 PM |

1 Comment »

Last glaciation in North America borrowed from this site. Isn’t it gorgeous?

Plotting continental divides on a map can produce some interesting patterns. Here’s a web page John pointed me to that considers the Gulf/Atlantic divide and the drainage divides across Georgia. Note the many parallel linear drainages across the piedmont and coastal plain, I’m guessing because of the longevity of this pattern.

If you’re in the mood to wander the web, you might also be interested in this blog that looks at GIS, geospatial technology, and, okay, I admit it, their intersection with archaeology. The blogger, Matt, posted a link to this nifty site with images constructed of the last 550 million years of North America’s surface geography, like the one above. This is roughly the period when humans arrived in North America, and we’re hip deep in arguments about whether they took sea routes or arrived via a proposed ice-free corridor along the Rockies. Of course, some recent publications have argued for a Pacific Coastal route that was less blocked by ice than shown here and there was no ice-free corridor. Stay tuned to the relevant journals, as this discussion will likely continue over innumerable beers. However, if another golden oldies bunch is right, a wave of hardy vagrants, whose descendents may or may not survived to meet later waves of immigrants, arrived 50,000 to 70,000 years ago, and that would have been earlier than this image.

Posted at 4:35 PM |

Comments Off on Web maps

The Prime Meridian, the one through Greenwich, England, doesn’t line up in Google Earth. As you can see, the meridian in this projection is east of the observatory, by about 100 meters. The reason:

The Prime Meridian, the one through Greenwich, England, doesn’t line up in Google Earth. As you can see, the meridian in this projection is east of the observatory, by about 100 meters. The reason:

This is not a mistake on Google’s part. The developers of Google Earth (originally known as Keyhole) chose to support the same coordinate system as that used by GPS technology known as WGS-84 World Geodetic System.

Click here for a technical explanation of all this. Basically, the earth isn’t a smooth, regular sphere, and GPS is so accurate, something had to give. So they shifted the Prime Meridian. And there’s also the contribution of continental drift….

Google Earth (it’s FREE), if you haven’t yet explored it, is fascinating—searchable satellite photos of THE WORLD! Add places to your personal list, or send them out to the Google community.

Trivia: the GPS system uses 25 satellites, each with two atomic clocks. Bob Burns turns 80 today (Happy Birthday, Bob!). Jack Finlayson has come through his surgeries okay.

Posted at 10:37 AM |

Comments Off on Prime Meridian

The term “abandonment” is often inaccurate and imprecise in archaeological discourse because it veils a range of behaviors in the past and assumes descendent communities have relinquished their present interests and claims in ancient places.

This bit of wisdom—and they’re so right!—is by Chip Colwell-Chanthaphonh and T.J. Ferguson (“Rethinking Abandoment in Archaeological Contexts” in The SAA Archaeological Record, Jan 2006, pp. 37–41).

Substitute “collapse” for “abandonment” and it’s still accurate.

Now you have some idea why Jared Diamond’s books annoy me so much. His perspective is reductionist and ignores the range of comparative data available, indeed he ignores much of the data assembled by ARCHAEOLOGISTS, and the analysis we have done on the issues he’s commented on, especially in Guns, Germs, and Steel and his new Collapse book.

(I’ll quit now before this becomes a full-blown rant!)

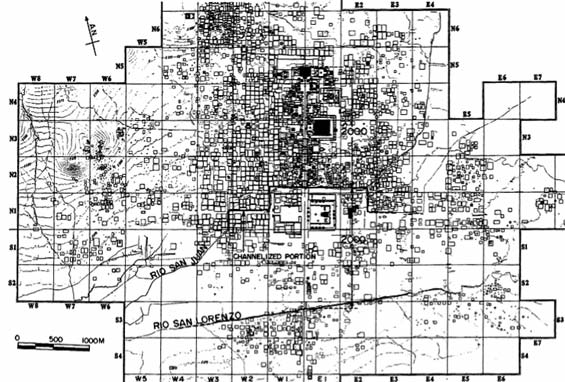

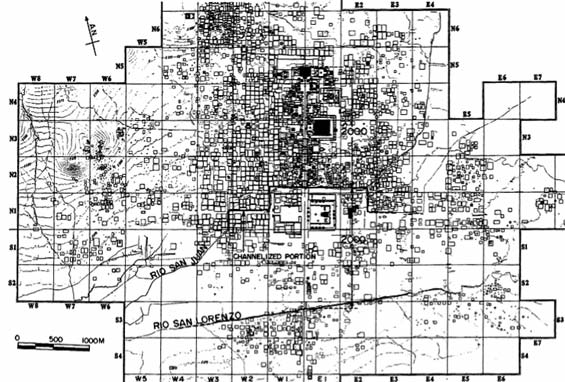

The map above is of the civic-ceremonial core and the surrounding residential compounds at the huge city of Teotihuacán, Mexico. It was drafted during the 1960s as part of the the Teotihuacán Mapping Project, headed by Rene F. Millon. (The squares are 1 km on a side, so this city is BIG!)

Many, including probably JD, say Teotihuacán was abandoned at the end of the Classic period. Well, the civic-ceremonial architecture (temple mounds and the like) were burned and not rebuilt, but the residential areas remained mostly inhabited for at least several hundred years after the conflagration. Yeah, I know this sounds like an incomplete story, and it is. Many Mexican archaeologists, and a few foreigners too, are still excavating and working to help us understand what happened at Teotihuacán.

Posted at 5:33 PM |

Comments Off on “Collapse�?

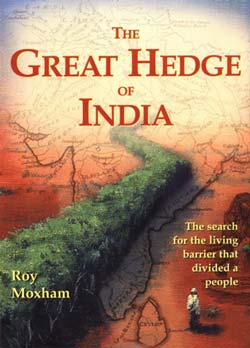

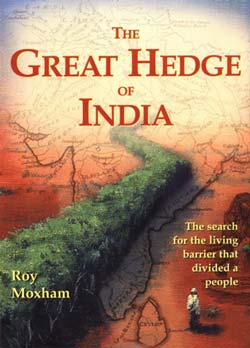

Apparently, even historians of Indian history are unaware that in the nineteenth century, a huge hedge, over 2300 miles at its longest, traversed much of India, built so the British could rake in even more cash from even the poorest Indians via a Salt Tax (and to a lesser degree, a tax on sugar). Take a look at Roy Maxham’s 2001 The Great Hedge of India (several editons, I think) for details.

Apparently, even historians of Indian history are unaware that in the nineteenth century, a huge hedge, over 2300 miles at its longest, traversed much of India, built so the British could rake in even more cash from even the poorest Indians via a Salt Tax (and to a lesser degree, a tax on sugar). Take a look at Roy Maxham’s 2001 The Great Hedge of India (several editons, I think) for details.

Scarce commodities or those with relatively few sources make good targets for control and taxation (good economic basis for political powergrabs). Salt can only be mined from or made in certain places (including along sea coasts), so the British were able to command construction of a barrier to trade into British India made of thorny plants, sometimes living (think acacias, prickly pear cacti, and euphorbias), or piled branches (harder to maintain but possible when plants wouldn’t take or were killed by vermin), with portals  every 4 miles or so manned by soldiers and customs agents. They abandoned the hedge in 1879, and its grade was reused for road beds (especially where it was elevated), or retaken for fields by farmers of adjacent plots. The hedge permitted collection of a tax on salt so high that made its cost prohibitive to most of India’s populace. At the same time, they taxed sugar passing the other direction.

every 4 miles or so manned by soldiers and customs agents. They abandoned the hedge in 1879, and its grade was reused for road beds (especially where it was elevated), or retaken for fields by farmers of adjacent plots. The hedge permitted collection of a tax on salt so high that made its cost prohibitive to most of India’s populace. At the same time, they taxed sugar passing the other direction.

Smuggling was common. Bags of sugar were loaded on camels that were rushed through the hedge. Others were lobbed over the hedge for collection by accomplices. Nevertheless, the British obtained a huge profit despite needing over 12,000 men to maintain and police the hedge.

Tidbits: Timbucktoo flourished because it controlled salt trade; salt tribute was taken in China as early as 2200 BC. Want more? Read the original….

Posted at 10:07 AM |

Comments Off on 2300-mile hedge

The Prime Meridian, the one through Greenwich, England, doesn’t line up in Google Earth. As you can see, the meridian in this projection is east of the observatory, by about 100 meters.

The Prime Meridian, the one through Greenwich, England, doesn’t line up in Google Earth. As you can see, the meridian in this projection is east of the observatory, by about 100 meters.

Apparently, even historians of Indian history are unaware that in the nineteenth century, a huge hedge, over 2300 miles at its longest, traversed much of India, built so the British could rake in even more cash from even the poorest Indians via a Salt Tax (and to a lesser degree, a tax on sugar). Take a look at Roy Maxham’s 2001 The Great Hedge of India (several editons, I think) for details.

Apparently, even historians of Indian history are unaware that in the nineteenth century, a huge hedge, over 2300 miles at its longest, traversed much of India, built so the British could rake in even more cash from even the poorest Indians via a Salt Tax (and to a lesser degree, a tax on sugar). Take a look at Roy Maxham’s 2001 The Great Hedge of India (several editons, I think) for details. every 4 miles or so manned by soldiers and customs agents. They abandoned the hedge in 1879, and its grade was reused for road beds (especially where it was elevated), or retaken for fields by farmers of adjacent plots. The hedge permitted collection of a tax on salt so high that made its cost prohibitive to most of India’s populace. At the same time, they taxed sugar passing the other direction.

every 4 miles or so manned by soldiers and customs agents. They abandoned the hedge in 1879, and its grade was reused for road beds (especially where it was elevated), or retaken for fields by farmers of adjacent plots. The hedge permitted collection of a tax on salt so high that made its cost prohibitive to most of India’s populace. At the same time, they taxed sugar passing the other direction.