End of Feb!!!!!!

Saturday, 28 February 2009

How can it be the end of February already?

Friday, 27 February 2009

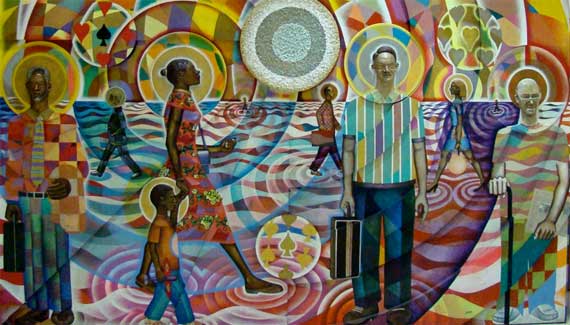

Huge, lovely mural at the airport….

Long story short: we took MARTA to the airport (or NGE’s take on it), and it was a Breeze! But, we didn’t take a flight!

So, you ask, why did we go down there?

Oh, we joined the Regenaxes for breakfast! Well, and a lot of laughing and conversation!

What fun!

Thursday, 26 February 2009

This tree is gnarled and old and heavily pruned, but the few blooms it has this year are huge and spectacular.

Is this a metaphor? Maybe for the desired outcome of all these economic and financial shenanigans*?

* No singular for this term of unknown origin….

Wednesday, 25 February 2009

I know you’re wondering: D Day is in June; what’s that whacky blahgger thinking?

Well, this is the spring D Day, I’m calling it, based on all the daffodils I saw on my walk today—including this one with a peachy-orange center.

Tuesday, 24 February 2009

Sad sad sad. Worse than the global financial situation. This is the house that burned the other day….

Our President bids us to look at our (national) finances with honesty and openness—i.e., to use critical thinking and to not exercise denial.

I heartily applaud that. Even though it’s painful.

I look at our household finances, and, um, it’s no fun to do that. Also painful. Actually: painful squared.

I suppose there’s another element in play here. Unlike our government, we’re cheapskates*.

Science comment: while species distribution has long been linked to climate, tada!, it’s not that simple. Instead, more complex issues may constitute the determining factor, as shown by this study of western hemlock distributions in western North America. Climatically similar areas may offer different competitive situations, as with more frequent fires and more disturbance-adapted species keeping the western hemlocks from proliferating in the Rocky Mountain region, as compared to the Pacific Coast region.

* Interesting word: cheapskate. The “cheap” part is from an Old English word referring to bargaining or trade, from the Latin caupo, or small trader/innkeeper. The “skate” part is from a term for a worn-out horse, or for a mean, contemptible, or dishonest person. According to the Mac dictionary….

Monday, 23 February 2009

The sun-angle is changing. I have hope for summer’s arrival.

Sunday, 22 February 2009

You end up with these rings from taking the rounds of orange out. They’re essential to the punch of this dish….

I saw this recipe yesterday (from Mr. Bittman, in the NYTimes), and have made it two days in a row; it’s a raving success! Yummy. Of course, I make it with only a smidge of olive oil, compared to the recipe.

It’s simple; throw some pitted black olives into the food processor. Add a bunch of fresh thyme leaves. Pour in a couple of teaspoons (or more, depending on how many olives you used) of olive oil. Whirr for just a short bit. Serve over orange slices.

Bittman says he got the recipe from Marco Folicaldi, who says it’s an olive purée, not a tapenade (no anchovies).

Saturday, 21 February 2009

The hyacinths are coming! The hyacinths are coming!

In my dreams I really write well—like Colin Thubron describing an ancient vehicle, still in service: “Already its body was disintegrating, half its dashboard had gone, its radio mercifully dead, and styrofoam belched from its seats.” That’s from pg. 62 of his Shadow of the Silk Road (2006). Here’s a longer passage from that volume (pg. 124–25):

The only purpose in the silk moth’s life is to reproduce itself. During its two-week existence it never eats and cannot fly. Instead this beautiful Bombyx mori lays eggs from which larvae as thin as hairs are born: offspring so light that an ounce of eggs yields forty thousand caterpillars.

At once they start to gorge ravenously. Their only food is the white mulberry, whose pollarded skeletons line the fields of Khotan*. Peasant families exhaust days and nights feeding them, with an ancient care which no machinery can match. Sightless, almost immobile, the silkworm has been reduced by millennnia of cultivation to a helpless dependence on humans. The caterpillars are like neurotic babies. They thrive only on fresh leaves, gathered after the dew has evaporated, and served to them, at best, every half-hour. Ideally the age of the mulberry shoots should coincide with their own.

In five weeks of frenzied feasting they consume thirty thousand times their weight at birth. The munching of their jaws makes a noise like rain falling. Centuries ago the Chinese noted that the colour of their forelegs anticipated the tint ofthe silk they would sping. Abrupt changes of temperature or lapses in hygiene, any sudden noise or smell wreaks havoc with their nerves, and they may die. But after a month each silkworm has multiplied its initial weight four thousandfold, and has swollen to a bloated grub, its skin tight as a drum, with a tiny head.

Then suddenly—when moulted to creamy transparency—the caterpillar stops eating. For three days the future silk flows from its salivary glands in two colourless threads which instantly unite, and it spins these about its body with quaint, figure-of-eight weavings of its head. Even after it has sealed itself from sight inside its shroud, it may sometimes be heard, faintly spinning.

Then comes the ‘great awakening,’ as the Chinese say. Within twelve days, locked in an inner chysalis, the wings and legs of the future moth like folded on its breast. Then it stirs and bursts with dreamy brilliance into the sun.

Here in Georgia we once had, locally-speaking, a large-scale silk industry. It was in New Ebenezer (founded 1736; the nearby original Ebenezer was founded in 1734), a settlement established by Protestant Salzburgers upstream from Savannah, ca. 1740. Read more here and here.

* Khotan, also spelled Hotan, is on the southwest edge of the Taklamakan Desert in far western China.

Friday, 20 February 2009

First, it was wild land.

Then, the Euroamerican landgrabbers founded Terminus, to be the end of the railroad coming south from Chattanooga. By 1842, it had 30 residents.

Then, Wilson Lumpkin asked that the town be named after his daughter, Martha, rather than himself. Terminus became Marthasville.

And, not long after, the community was incorporated in 1847 as Atlanta.

Then came the War of Northern Aggression, when Union soldiers torched fair Atlanta.

Rising from the flames, residents chose the phoenix as the symbol of the city.

And the reason for this historic recitation*? Over 7–22 March, the Atlanta Preservation Center presents a “Citywide Celebration of Living Landmarks” (buildings, not people). The connection: this is called Phoenix Flies.

I must confess I hear that name and I think of a summer street in postbellum Atlanta strewn with road apples and their attendent clouds of busy insects.

Thursday, 19 February 2009

You’ve heard of those studies using indirect methods (e.g., diaries, letters) to reconstruct climate patterns? I offer this photo from five years ago this day. I know it isn’t a close-up, but it still looks approximately like the trees do here today.