Musings

We’re finishing up the run of pale pink azaleas out front.

And…another “residual”…of a detail shot…from the Cluny, of a 1467 Mullenheim family arms stained glass piece. Love the shading, 3-D effects, color choices, whole ball of…not-wax.

Posted at 10:22 PM |

Comments Off on There goes April

We collected by far the most images at the Cluny. Or, many call it the Cluny, but the name is actually Musée National du Moyen Âge—Thermes et hôtel de Cluny. Cluny was a Benedictine abbey 225mi SSE of Paris, near Mâcon, and this was their “townhouse” in Paris (begun in the 1300s and rebuilt around 1500). It was built atop Roman baths, hence the second part of of the name…. The first part refers to the Middle Ages, which is the temporal focus of the collection. The nearest subway station honors the arts with tile versions of artists signatures on the ceiling.

Euros are being spent on revamping parts of the complex, and the entrance currently is through a narrow portal into a non-symmetrical quadrilateral courtyard (with a security tent…open your handbag, ma’am, please (only in French)).

Many stone walls of the abbey are…very clean, no stucco, no paint. Stairwells and so on have been added to make the buildings into a museum.

We didn’t make it into the Sainte-Chapelle (near Notre-Dame), but we did get to see about two dozen small window panels from it…very close up. Love the detail on this bull and man’s face.

Also on this murderous knight and his non-plussed horse.

This is detail from a capital from the church in the abbey complex of Saint-Germain-des-Prés (Paris), showing Daniel tangling with the lion. This abbey was founded in the 500s, and this stonework dates to 1030–1040. Through the Middle Ages, the abbey owned quite a chunk of land on the West Bank.

The Cluny collection may be best known for the La Dame à la licorne/the lady and the unicorn tapestries. There are six, with five obviously pertaining to the senses—smell, touch, taste, hearing, and sight. The sixth has the words À mon seul désir…what the soul desires, so is a bit enigmatic—maybe love, joie de vivre, something along those lines. This is a detail from the sight one, with the lady holding a mirror for the unicorn to see its reflection. The tapestries are huge.

Stained glass detail (I/we did not record the source).

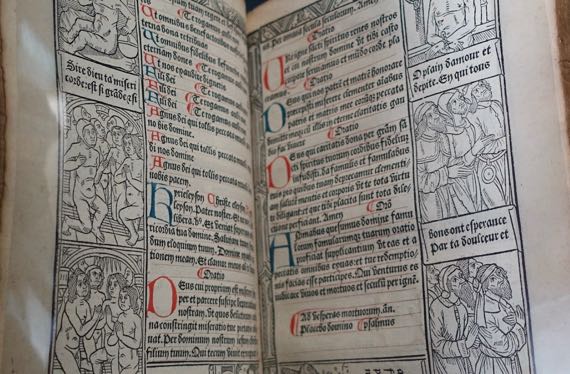

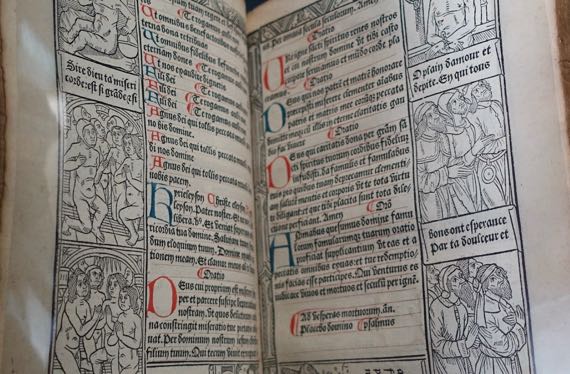

1490–1493 Book of Hours devotional by Antoine Vérard, who was first to combine printed black text with hand-drafted colored “capital” letters, thereby combining the best of the new printing process with the artistic elegance of the old by-hand-only methods.

This is a detail of a reliquary of St Anne, and she is holding a mini-reliquary. That does make the point, doesn’t it?

The chapel of the Cluny monastery complex is stripped of its decorations and has only a few museum pieces in it. The emptiness and bare walls are striking. Footsteps echo loudly.

From an upper level I could see into the garden. We were only able to enter a small portion that did not include this part.

From the street, here is Cluny ruins atop thermae ruins (I think).

Somehow we made it into another church, the Église Saint-Séverin. Séverin apparently was a hermit in Paris’s early Christian times. Behind the altar (and behind me for this photo) are six large stained glass windows dating to 1970, with modernist (not realist) color panels that we both liked.

And one more church…near where we’re staying…the Église Saint-Louis-d’Antin. It began as a Capuchin establishment about 1775. Most of the rest of the complex became a lycée in 1883.

What a Sunday.

Posted at 3:22 PM |

Comments Off on Sunday best

Meet Marianne. She’s the personification of the Republic of France, and the visual anchor of Paris’s Place de la République. In particular, she represents the dissolution of the monarchy and the installation of the republic. Power to the people (more or less). A female figure representing liberty goes back to the later 1700s, and became a widely used icon with the 1789 storming of the Bastille, a prison and symbol of royal authority in central Paris.

This is not far from the neighborhood of the blown-up nightclub, etc., and it has been and continues to be a place of political statements and demonstrations.

Below Marianne and still above eye level is an oversized lion guarding a ballot-box. More République. Today he had golden tears.

And, on the surface at knee level, many candles and living and plastic/fabric flowers and plants. The topics addressed in word and picture range around the world.

We chose the Musée des Arts et Métiers for today’s brain teaser. It is a museum of industrial design including models of large, complex things (steel furnace), and smaller complicated mechanical items (measuring devices). They sent us to the attic to work our way through the galleries and descend…. Loved the open beams there….

1713 double horizontal sundial.

1825 clock, close-up of upper section.

Bobbins on a mechanical weaving machine.

Detailed diorama of the building of the Statue of Liberty in New York harbor.

We descended a final staircase, very fancy, marble, wide, and highly decorated. Above us, curators have installed Clément Ader’s Avion/Éole III (1897), with the form modeled on a bat, with feather-shaped propellors. It crashed on its first attempt at flight, and was restored in the 1980s. It does look rather like a modular bat.

Through a hallway of transportation (this is a Peugeot), we headed for the Chapel of Saint-Martin-des-Champs, a part of what once was the second-most important priory in France, and now within the museum complex. Most of the complex was removed during the Revolution.

The “front” of the church is empty, very interesting, with a pendulum slowly moving, showing the earth’s revolutions.

The bulk of the church-space has exhibits, which include a small engineering wonder—stairs and glass exhibit-floors extending four stories (or so) up. While I had some trepidation about the height, I was glad to get so close to the stained glass panels.

This museum—industrial design from start to finish….

Posted at 12:00 PM |

Comments Off on Industrial design + old church

First stop (after coffee): the new Les Halles. Once the site of Paris’s huge fresh food market, it’s been a shopping mall for decades, and was refurbished last year, with this remarkable swooping roof. A new garden outdoors is only partly open.

In the moving crowds, we spotted this clot that wasn’t moving. Autograph- and selfie-seekers. The tall guy is security. The ombre-dreads fellow is the celebrity. We didn’t recognize him. Musician, as he was signing CDs….

Also facing the Les Halles area, this old church, Saint-Eustache, built between 1532 and 1632, although there was a parish church here by 1223. Contrasting centuries and architectural styles….

We kept moving, crossing onto the Seine’s western isle. We enjoyed a few minutes on a sturdy bench among the leafing-out chestnuts, preparing ourselves for things to come.

Of course, next was Notre Dame, and this is the view I always remember, perhaps because it was the angle I first saw it…and realized that the façade is so truncated without the steeples.

Over several significant construction periods, expansions and refurbishments, the building is what we see today. I remember most the façade, this rose window, and…

…the flying buttresses.

Nearby, without an extensive plaza facing and highlighting the building is the 13th-C Sainte-Chapelle, the royal chapel known for its beautiful glass windows. Which I have heard about and not seen—45-minute wait on a cloudy day…we passed. Next time, we vowed….

Also, we were hungry. So we strolled down to the eastern isle and a brasserie we first visited in 1989. Simple Parisian food, well made.

Then, heading toward a subway stop, we saw a coffee shop we enjoyed on our last visit. With pastries. Yum, raspberry cheesecake-tart.

Many of the parked motorcycles have these blankets; I remember fewer in Rome. A warmer, drier way to ride….

Posted at 10:22 PM |

Comments Off on Core Paris

We added serendipity to our planning, spurred by the diminution of water to our flat. Management claimed it was a problem for all their properties and across the immediate area. (Shower later, I thought.) So, we headed to Starbucks for an energy boost, then took the train over to the V&A, founded 1852 and now with 145 galleries (I read that; I did not count even the ones I entered). Whew. Here’s a tiny sampling of the sample that we saw.

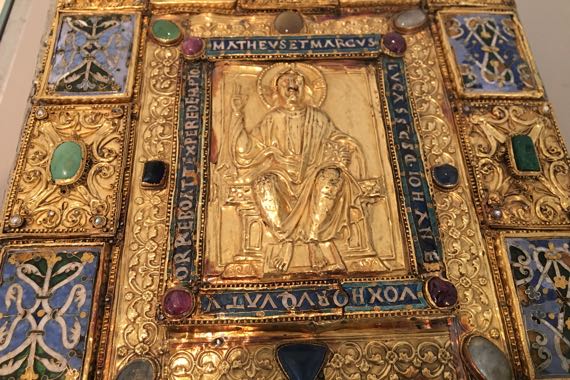

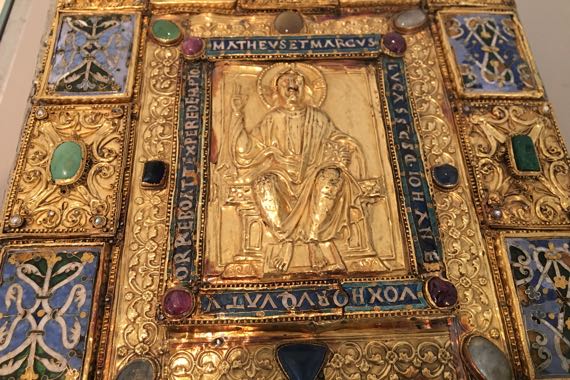

Sion gospel book, cover/binding dates to ~AD 1140-1150; central panel of Christ probably later.

Carved ivory panel portraying a pagan (non-Christian) ceremony probably celebrating Dionysus, Symmachi family, Rome, AD 400. This was after Constantine declared for Christianity for the Empire, and during the time that both persisted. Heavy-featured priestess, no?

Tomimoto Kenkichi painted pottery plate, 1931. Friend of Bernard Leach’s from Tokyo.

Pablo Picasso, 1950–51, “Cavalier sur sa Monture.” On that web page, the V&A says, “Picasso successfully challenged traditional divisions in the arts world and made a major impression on a new generation of potters.” (It’s Picasso, so it’s a big pic.)

Ceiling of the ante-room of the 1877–78 home, The Grove, in Harborne, near Birmingham. Designed by John Henry Chamberlain; woodwork by Samuel Barfield. The V&A got the room just before the building was demolished in the mid-1960s.

Now somewhat faded due to the use of natural dyes, this hand-knotted piece was co-designed by William Morris and John Henry Dearle, and is called the Bullerswood Carpet, as it was made for John Sanderson’s house in Kent, called Bullers Wood some places. The design elements are drawn from nature. Date:1889.

View through dirty window. And this is paved, clean London. Think what it used to be like….

On to Harrods (founded 1834; apparently now owned by Qatar Investment Authority), first for lunch and then to browse. This was my lunch, grilled Dover sole with hollandaise sauce, a glass of sancerre, and a side salad of rocket and shaved parmesan, with a lovely, light vinaigrette that included fine-chopped shallots. Oh, yum. We went in honor of the pre-Al-Fayed history, and the extensive offerings. Probably won’t go back—too much merchandise with Harrods imprinted on it and too commercial in general; however, food tasty and high-quality in food hall and this seafood grill.

Bluetooth speakers with bone-shaped remote.

“Army men” display in Toys section.

Off to nearby Hyde Park to sit in the sun, and…

…heard an incoming clop-clop, and had mounted police come by our sun-bench…

…and saw a meadow of bluebells foregrounding…police vehicles as we left the park. We can say: police presence, no?

Water’s back on and we’re recovering in our flat (all feet are tired; whole of The Guru is tired.)

Posted at 2:06 PM |

Comments Off on Serendipity and plans

The Severn Bridge we took into Wales opened in 1966. I bet traffic patterns changed immensely, even with the substantial toll. In 1996, the Second Severn Crossing opened; set a bit downstream, it especially carries vehicles flowing to/from southwest Wales, including Cardiff and Swansea. The powers-that-be had the two combined into a single concession to share toll collection and debt repayment. So, we entered Wales on the old bridge (not that old), and left on the new bridge. Bye-bye Wales, we are London-bound with two Roman stops en route.

Discovered in 1818, this modest Roman villa commanded the upper area of a smallish drainage, and was built into a hill. Construction began in the AD 250s, and the place was abandoned in the early 400s, when the Roman military pulled out of Britannia. The mosaics are under the roof. The place was ours to visit, quiet except for distant pheasant squawks and generic country sounds.

Chedworth Roman Villa, on the other hand, was bustling with docents and vendors, school groups, walkers, and generic tourists. The complex grew over about the same period as the previous villa, and also was set into a hill’s upper slope. This complex became much larger, and much more architecturally elaborate. It ultimately had two bath areas, for example. In this view of the metal maquette, uphill is to the lower right, with the lower, larger courtyard planted into a garden that opens to the upper left (actually east) and views of the valley.

This was among the earliest mosaic floors at Chedworth, along a passageway in the upper “horizontal” bank of rooms that faced the valley (late AD 200s). The earliest construction was up here, three separate buildings that eventually became a single “range” of attached rooms.

In the early 300s, this elaborate dining room was added, with considerable wealth invested in the floor. This was a typical choice of elite homeowners, as the dining room was the principal location for entertaining (plus the decorative gardens).

Love the mushroom pillars of the hypocaust floor…. It seems to me that more rooms than in a Rome-area Roman villa had heated floors, I’m assuming because they had the water/firewood to make the heat, and because it was colder than Rome here, and this was how elites made living in the colonies more like life at the imperial center, and thus more Roman.

Just one detail from the museum, from the display of impressions in roof tiles. The tiles were made locally, but probably not on the villa property. These are ox-hoof impressions. Other displayed examples were dog, cat, human fingers….

Within ten miles of Chedworth are eleven villas, including Great Whitcombe that we visited earlier today. Chedworth is between two roads that radiate in a northerly direction from Cirencester. We misheard our navigation-voice say that place as Siren-sister (hence today’s title); it’s pretty close. While that sounds like the Roman name, it isn’t; the Roman name was Corinium Dobunnorum. During the time of the villas, Corinium also had many domestic complexes with elaborate mosaic floors and other markers of wealth. Money could be made here, both through agricultural pursuits and through regional and long-distance trade. Anyway, this modern road follows Fosse Way, the Roman route to the NNE out of Corinium. The complete Fosse Way went NNE from Exeter to Lincoln (today’s names).

En route around Heathrow’s runways to the car rental return, we again noticed these little human transporters on a rail. I only got this one crappy picture, at a distance. These self-driving units are called pods, and the service is aimed at business travelers, linking a special parking lot with Terminal 5. It opened in 2011.

Our London home is an Ikea special. The folding chairs are actually from Ikea. If you have long arms, you can almost make coffee from the bed. We have a window with a park view and wifi; life is good.

We took off for the Thames and points en route. We thought we might take the train back, but hoofed it the whole evening. Here’s a fountain in a nearby park (not our window-park). We saw several groups sitting on the grass enjoying an early meal/snack.

We saw the Thames in the last of the day’s light. And heard Big Ben chime at 8pm.

Turning north, we entered Trafalgar Square. Fountains. Spires. Blocky buildings. Man-on-horse statues.

And…Admiral Nelson towering over a red glowing Roman arch. Art. The Guardian says it’s a Carrara marble replica of Palmyra’s Arch of Triumph, recently destroyed by Daesh/Isis. It is here for three days and gorgeously lit.

Posted at 10:22 PM |

Comments Off on Siren-sister

Fog on the moor this morning. Love the visual contrasts of, from front to back, the uncultivated moor, the quilt of fields separated by hedges, the sea, the Wales coast, and the muted sky.

Quick stop in Clevedon to see several places used as the town in “Broadchurch”—including this church, St Andrews in real life. This is a living church, as it were, with a gravedigger (man and machine) busy opening a new spot and prayer books shelved by the door.

Then, farther up the coast, we turned west to cross this Big Bridge, the pleasure for which we paid the princely sum of £6.60. Of course, leaving Wales is no charge…just a one-way fee collection plan…perhaps to encourage the English to leave but not to visit?

Welsh lesson: ARAF means slow. Sometimes they’re in the other order. (I was going to make the title of this post “post wan,” which translates as “weak bridge,” a not uncommon phrasing on a sign on a country lane.)

And, now for Tintern’s church ruins. It is mostly commonly referred to as an abbey, and it was, but most photos are, frankly, not of the monastery, but of the church.

First, the window opening above the east, altar end of the main hall. Second, the newly restored upper window area of the opposite, west (door) end. North transept, wall of high window openings extending to west end.

The light was transcendent.

Today is our first visit to Wales. Signs are different—bilingual. Sheep seem the same to us non-shepherds.

And this is the National Assembly building in the dock-front area of Cardiff. Shipping is not what it used to be and this zone is being repurposed to draw locals and visitors. While somewhat commercialized, there are also stunning modern and historic buildings. And glittering water, wheeling gulls, and, for a while just for us(!), late-afternoon warm-toned sunshine.

Here’s a closeup of a living fence, mentioned yesterday. This one has the uprights just bent to the side, rather than all the way horizontal. After growing, it has the same effect of making a latticework impenetrable to sheep, cattle, and people. Small birds, rodents, and other small creatures may well make their home here….

Posted at 10:22 PM |

1 Comment »

Whatever you think you know about Tintagel Castle, it’s probably wrong. The King Arthur association, no chance. The rocky almost-island has plenty of ruins, mostly dating to three periods, the Dark Ages (here AD 500–600s, roughly), the 1200s, and to Victorian times. The DA ruins are pretty humble and meager. While the landform is defensible, there’s little else to recommend it—not much area to grow food and everything’s rocky, although the harbor situation for small watercraft is workable if the seas are relatively calm (says this landlubber). The “castle” dates to about 1230, including the ruins of a Great Hall and Chapel (the most recognizable architecture). The Great Hall had to be modified as part of it slid into the sea not long after it was constructed. The rest of what commonly constitutes a castle—not here or only small bits. The Victorian modifications look like versions of a folly to me….

Here’s the Great Hall…. Both these pictures show Tintagel’s most salient feature: elevation changes. This is rough terrain. Note that the bridge below (far below) my shadow is steps—not flat. See: terrain!

We were glad it was only breezy (and not windy) and not rainy (and slick underfoot) during our Tintagel visit. BTW, that big, chunky, rectangular building on the far hill is a hotel. Great location for them; bit of an eyesore from Tintagel.

Wind generators…all busy generating—none still.

And on Exmoor (our last moor, I think), elaborate hedging…and the secret of how they’re made was revealed to us along this stretch—no photos; too fascinating to snap, just looked. So, here’s the secret to that dense vegetation. About 10cm very upright trees in the existing hedge are cut in a not-quite-vertical slice, so that the top is still attached to the root. Then, the branches are sliced off the tops, which are laid down along the top of the existing hedgerow (two parallel rows), and tied together to keep them from springing back up or shifting out of alignment. They must subsequently send up new verticals, making the dense hedgerows we see, along with the horizontals below the verticals.

The hedging on the left has been trimmed mostly I think to give drivers better line of sight, although also to keep branches from brushing vehicles.

Exmoor pony. That’s Wales on the other side of Bristol Channel, below the line of clouds. We go there tomorrow.

Since it’s a moor, standing stones, right? These two are leaners at this point. And someone’s planted daffodils. We have been enjoying daffodil and primrose season in southern England. We are so lucky with the weather (fingers crossed for the coming days).

Posted at 4:52 PM |

1 Comment »

St Michael’s Mount, established by monks from the four-times larger Mont Saint-Michel off the Lower Normandy coast in the 1200s. Evidence still turns up of Neolithic and Iron Age use of this prominent landform. Castle closed. Garden closed. Parking prices steep at £3.50 and £4. Rain setting in, so we drove on. (Honeymoon revisit).

The road destroyed half of this large stone-walled burial chamber (probably Neolithic); no doubt it had been looted centuries before. Still: massive stones. One looked like it had deliberate large pits made in it. (Info on-the-net suggests this is a copy (“cups”), and the original is museum-ed.)

In a nearby field is the Merry Maidens stone circle, which has several names and many stories associated with it. What we see today is in part a fanciful (and likely earnest) reconstruction. Several outlying stones are in other fields. Loved having the rainbow join us.

With rain, you can find…mud on road.

And ducks near ponds. These kindly drifted off the pavement so we could pass, and returned as soon as we were by.

This is Cornish tin mining country. There must have been terrible environmental degradation during that time. These sentinel chimneys (stacks they call them) are scattered about. Most have this shape and the two-toned appearance.

We went to Port Isaac! You may know it as Port Wenn from the British TV series “Doc Martin.” His surgery is to the right. And don’t even try to peek in the windows. Tide was in. Parking costs still high here—and you need coins for the P&D machine, although they tried to offer a smart phone option—but the interface was crap.

Next town over is Port Quin, now mostly ruins and cottages, and not many of either. And the coast path, of course. The building to the left was the pilchard palace, where they aged(?) the pilchards. The row of square holes was for beams that pressed the fish in the barrels, if I understood correctly. Must have smelled just fine all across town. One must have hoped for the near ever-present wind.

View from our room under the eaves (and in our price range). That’s Port Isaac in the bay. And we can hear the wind on the slate roof.

Posted at 10:22 PM |

Comments Off on Clockwise Cornwall

Of the five castles/fortifications planned to protect the mouth of the River Fal, only two were built, and only this one has the flavor of its architectural roots from 1540–1542. This is St Mawes Castle.

It faces its much modified and much larger opposite number across the river-mouth, now Pendennis Castle.

The interior is mostly empty, although cannons still point out their special windows on the ground floor. On one floor curators have placed artful dummies who mostly look like they are waiting for the order to fire.

We opted to skip Falmouth and Pendennis Castle, taking a car-ferry, yippee! (Don’t remember seeing that icon before.)

Yup, the King Harry Ferry. £6 please, one way (£8 return, a great deal for those traveling in circles).

Found a town named Gweek. The car soon filled with no end of puns and word games.

This installation at Goonhilly is now technology so old the contract has been let to remove it. Last chance to see it….

Hiked out this long peninsula with two artificially narrowed bottlenecks. It was used as a fortified promontory fort in the Iron Age, or so They say. The name must have had the word “wind” in it in some form.

Lizard point is Cornwall’s and England’s southernmost (on the mainland). The name is from the pre-Celtic/Cornish lis meaning court and ard/ardh meaning high. The name thus refers to a locally important building here.

And, what a surprise, right there on the north side of Lizard (town)! Not green…just saying. [Sorry; sign says GREEN COTTAGE.]

Posted at 10:22 PM |

2 Comments »